Documento de consenso sobre el manejo clínico de la comorbilidad neuropsiquiátrica y cognitiva asociada a la infección por VIH-1

Julio 2020

Notas de la Versión:

Coordinadores y revisores

| Ignacio Pérez Valero |

Facultativo especialista en Medicina Interna – Enfermedades Infecciosas. Unidad de VIH, Servicio de Medicina Interna, Hospital Universitario La Paz – IDIPAZ, Madrid. |

Jordi Blanch |

Facultativo especialista en Psiquiatría y profesor asociado. Servicio de Psiquiatría y Psicología, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona – IDIBAPS, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona. Director del Pla Director de Salut Mental i Addiccions, Generalitat de Catalunya. CIBERSAM. |

Redactores por orden alfabético

| Pablo Bachiller Luque |

Facultativo especialista en Medicina Interna – Enfermedades Infecciosas. Servicio de Medicina Interna, Complejo Asistencial de Segovia, Segovia. |

Isabel Cuellar Flores

|

Facultativo especialista en Psicología Clínica e investigadora. Servicio de Pediatría, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid. |

| Helen Dolengevich Segal | Facultativo especialista en Psiquiatría. Servicio de Psiquiatría, Hospital Universitario del Henares, Coslada. |

| Esther García Almodóvar | Facultativo especialista en Medicina Interna – Enfermedades Infecciosas. Servicio de Medicina Interna, Hospital Can Misses, Ibiza. |

Miguel Ángel Goneaga

|

Facultativo especialista en Medicina Interna – Enfermedades Infecciosas. Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas del Hospital Universitario Donostia, Guipúzcoa. |

Alicia González Baeza |

Psicóloga investigadora y profesora asociada. Unidad VIH, Servicio de Medicina Interna, Hospital Universitario La Paz – IDIPAZ, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid. |

Lorna Leal Alexander |

Médica investigadora asociada. Servicio de Enfermedades Infecciosas – Unidad VIH, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona – IDIBAPS, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona. |

María Martínez Rebollar |

Médica investigadora asociada. Servicio de Enfermedades Infecciosas – Unidad VIH, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona – IDIBAPS, Universidad de Barcelona. |

Marta Montero Alonso |

Facultativo especialista en Medicina Interna – Enfermedades Infecciosas. Unidad de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitario y Politécnico la Fe, Valencia. |

José A. Muñoz-Moreno |

Psicólogo investigador. Fundación Lucha contra el SIDA, Servei de Malalties Infeccioses, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona. |

José A. Muñoz-Moreno

|

Psicólogo investigador. Fundación Lucha contra el SIDA, Servei de Malalties Infeccioses, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona. |

María Luisa Navarro Gómez |

Facultativo especialista en Pediatría y profesora asociada. Sección de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Servicio de Pediatría, Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid. |

Rosario Palacios Muñoz |

Facultativo especialista en Medicina Interna – Enfermedades Infecciosas y profesora asociada. UGC de E. Infecciosas, Microbiología Clínica y Medicina Preventiva, Hospital Virgen de la Victoria – IBIMA, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga. |

Daniel Podzamczer |

Facultativo especialista en Medicina Interna – Enfermedades Infecciosas. Jefe de la Unidad de VIH e ITS, Servicio de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge – IDIBELL, L’Hospitalet. |

Guadalupe Rúa Cebrián |

Psicóloga General Sanitaria. Instituto Intra-TP. Instituto de Investigación y Tratamiento del Trauma y los Trastornos de la Personalidad, Santiago de Compostela. |

Juan Tiraboschi |

Medico investigador asociado. Unidad de VIH e ITS, Servicio de Enfermedades Infecciosas, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge – IDIBELL, L’Hospitalet. |

CONFLICTO DE INTERESES

Ignacio Pérez Valero ha recibido pagos por ponencias, consultorías y por la coordinación de proyectos de FMC de Gilead Sciences, Janssen-Cilag, MSD y ViiV. Igualmente, ha sido investigador coordinador de los estudios GeSIDA 9016 y GeSIDA 10418, financiados respectivamente por Gilead Sciences y Janssen-Cilag.

Marta Montero Alonso ha efectuado labores de consultoría para AbbVie, Janssen Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme y ViiV Healthcare, y ha recibido honorarios por charlas de AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme y ViiV Healthcare.

Pablo Bachiller Luque, Isabel Cuellar Flores, Helen Dolengevich Segal, Esther García Almodóvar, Miguel Ángel Goneaga, Alicia González Baeza, Lorna Leal Alexander, María Martínez Rebollar, José A. Muñoz-Moreno, María Luisa Navarro Gómez, Rosario Palacios Muñoz, Daniel Podzamczer, Guadalupe Rúa Cebrián y Juan Tiraboschi no han reportado ningún conflicto de interés en relación con la elaboración de este documento.

NOTA

Algunas de las Recomendaciones terapéuticas indicadas en este documento no están aprobadas en ficha técnica, pero el Panel las recomienda en función de los datos publicados al respecto. Cada facultativo prescriptor debe conocer las condiciones para la prescripción de medicamentos cuando se utilizan en indicaciones distintas a las autorizadas (Real Decreto 1015/2009, de 19 de junio, por el que se regula la disponibilidad de medicamentos en situaciones especiales).

1. INTRODUCCIÓN

Los Documentos de Consenso de GeSIDA sobre el manejo de alteraciones psiquiátricas y psicológicas y de los trastornos neurocognitivos asociados al virus de inmunodeficiencia humana tipo-1 (VIH) llevaban sin actualizarse desde hace 5 y 7 años respectivamente. Durante este tiempo, muchos de sus contenidos y Recomendaciones habían perdido su vigencia. Por este motivo la Junta Directiva de GeSIDA decidió en 2019 acometer una revisión, actualización y unificación del contenido de estos dos documentos de consenso, fruto de la cual nace el presente documento.

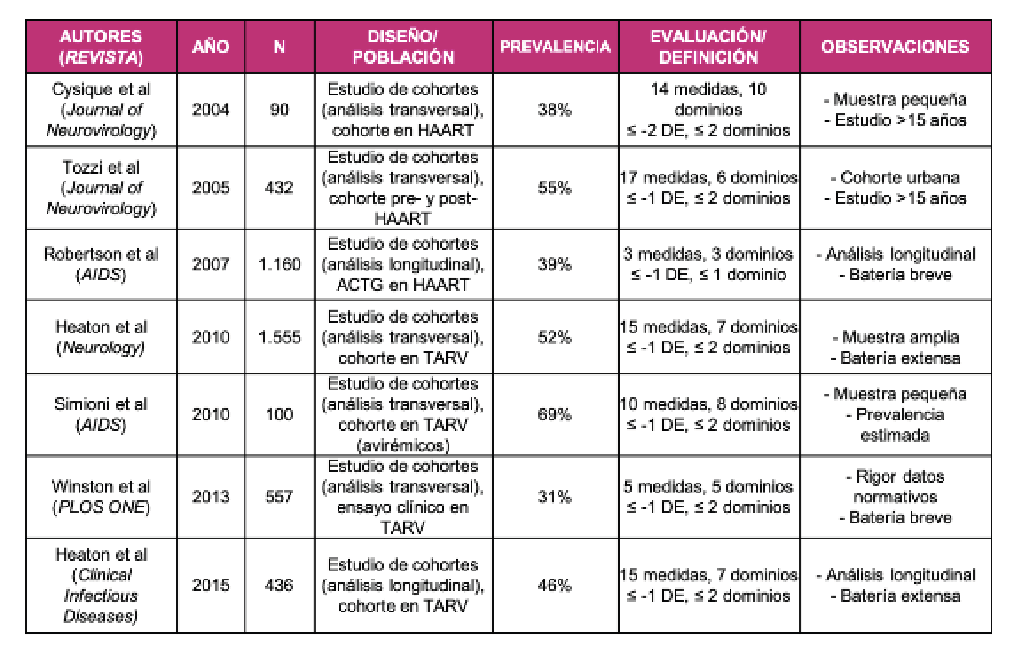

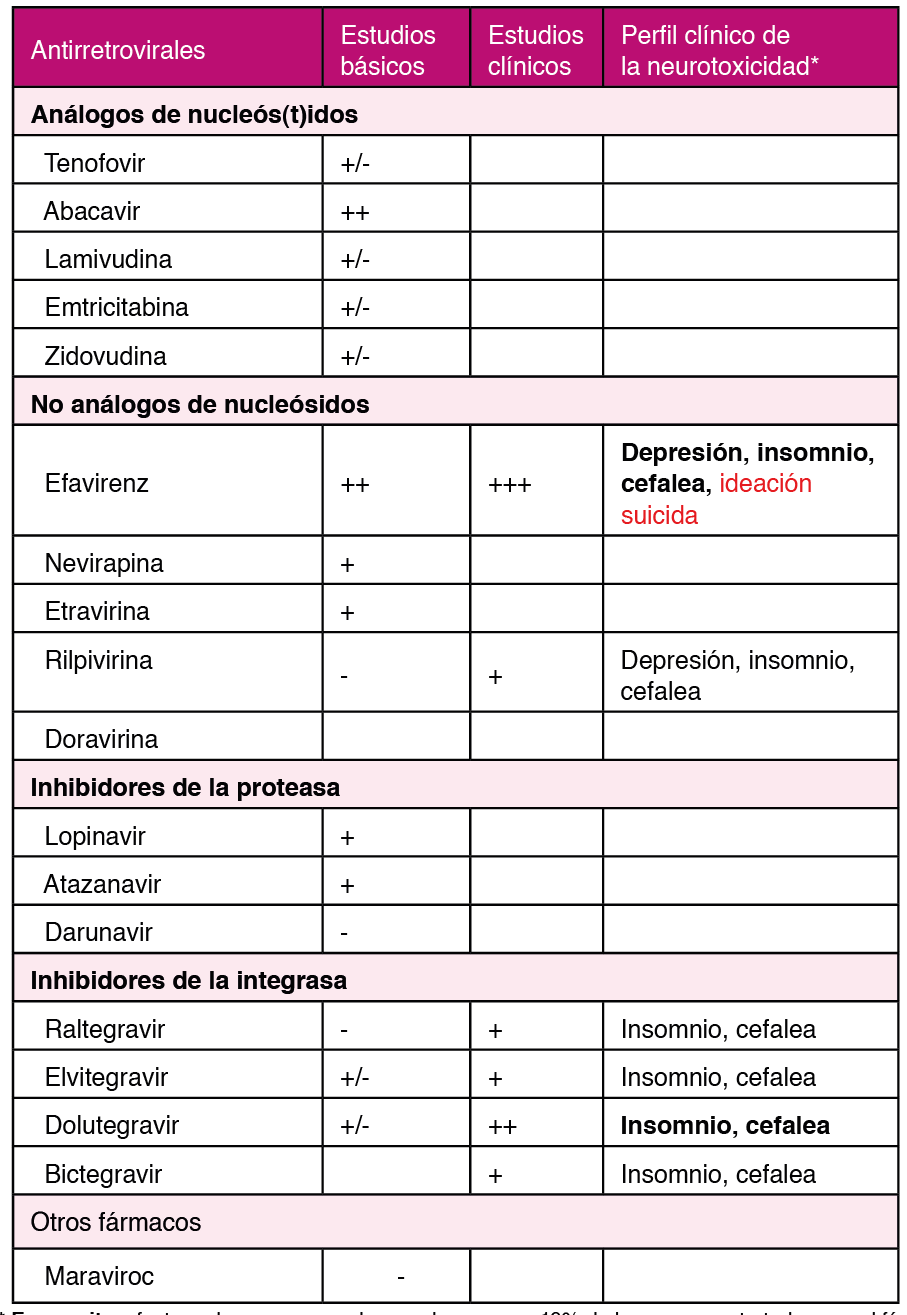

Desde la publicación de los documentos previos hasta ahora muchas son las cosas que han cambiado. Hemos asistido a la comercialización de fármacos antirretrovirales (ARV), como los inhibidores de la integrasa, más potentes y con menos interacciones farmacológicas. Esto ha conducido a que aspectos hasta entonces cruciales como la penetrabilidad del tratamiento antirretroviral (TAR) en el líquido cefalorraquídeo (LCR) o la interacción del TAR con el tratamiento psicofarmacológico sean cada vez menos relevantes y que otros aspectos antes menores como la neurotoxicidad asociada al TAR hayan adquirido una mayor relevancia. También hemos asistido a un envejecimiento progresivo de las personas que viven con VIH en nuestro país que ha favorecido el aumento de las comorbilidades neuropsiquiátricas y de los fenómenos de declive cognitivo, secundarios al neuroenvejecimiento.

El panel de expertos del presente documento ha intentado dar respuesta a esta nueva realidad actualizando sus Recomendaciones para el manejo de los trastornos neuropsiquiátricos y cognitivos que presentan las personas que viven con VIH en base a las siguientes tres premisas: El rigor científico, la experiencia clínica y su aplicabilidad en las consultas que atienden a las personas que viven con VIH en nuestro medio.

2. METODOLOGÍA

El presente documento de consenso ha sido elaborado por un panel de expertos designados por la Junta Directiva de GeSIDA entre sus socios y colaboradores. El panel del documento estaba integrado por dos coordinadores y 15 redactores. Las funciones encomendadas a los coordinadores han sido: 1) Definir los capítulos del documento y designar a los redactores responsables de cada uno de ellos; Y 2) Revisar el contenido de cada capítulo y dar uniformidad al documento. Las funciones encomendadas a los redactores han sido: 1) Revisar la literatura científica, redactar el capítulo o capítulos asignados y proponer Recomendaciones de práctica clínica; Y 2) Revisar el documento y ratificar su conformidad con las Recomendaciones establecidas por el panel.

Las normas establecidas para la revisión de la literatura comprendieron artículos indexados en Pubmed en lengua inglesa o española y comunicaciones a congresos presentadas en los últimos 5 años, siendo la última fecha de revisión diciembre de 2019. Las Recomendaciones de práctica clínica establecidas para cada sección del documento fueron propuestas por cada redactor, revisadas por los coordinadores y ratificadas por los miembros del panel. En el caso de que una recomendación no contase con la unanimidad del panel, este hecho quedará reflejado en el documento.

El documento, una vez finalizado, fue sometido a revisión por parte de la Junta Directiva y tras obtener su visto bueno, fue publicado en modo borrador en la página web de GeSIDA, estableciéndose un periodo de alegaciones abierto a los socios y colaboradores de GeSIDA. Las alegaciones recibidas fueron valoradas por el panel y en el caso de considerarlo pertinente, fueron incluidas en el documento final.

2.1. MÉTRICA UTILIZADA PARA GRADUAR LAS RECOMENDACIONES

Las Recomendaciones de estas guías se basan en la evidencia científica y en la opinión de expertos. Para graduar la evidencia de las Recomendaciones incluidas en el presente documento ha utilizado la misma metodología utilizada en otras guías de GeSIDA como la de manejo del tratamiento antirretroviral. Ver Tabla 1:

Tablas:

3. ABREVIATURAS

ACVA ARV BHE |

Accidente cerebrovascular agudo Fármacos antirretrovirales Barrera hematoencefálica |

| CHAR- TER | CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effect Research |

DM |

Diabetes mellitus |

DV |

Demencia vascular |

EA |

Enfermedad de Alzheimer |

HTA |

Hipertensión arterial |

IADL |

Instrumental activities of daily living |

ISRS |

Inhibidores selectivos de la recaptación de la serotonina |

ITS |

Infecciones de transmisión sexual |

LCR |

Líquido cefalorraquídeo |

MDMA |

3,4-metilendioxi-metanfetamina |

MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

PAOFI |

Patient’s Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory |

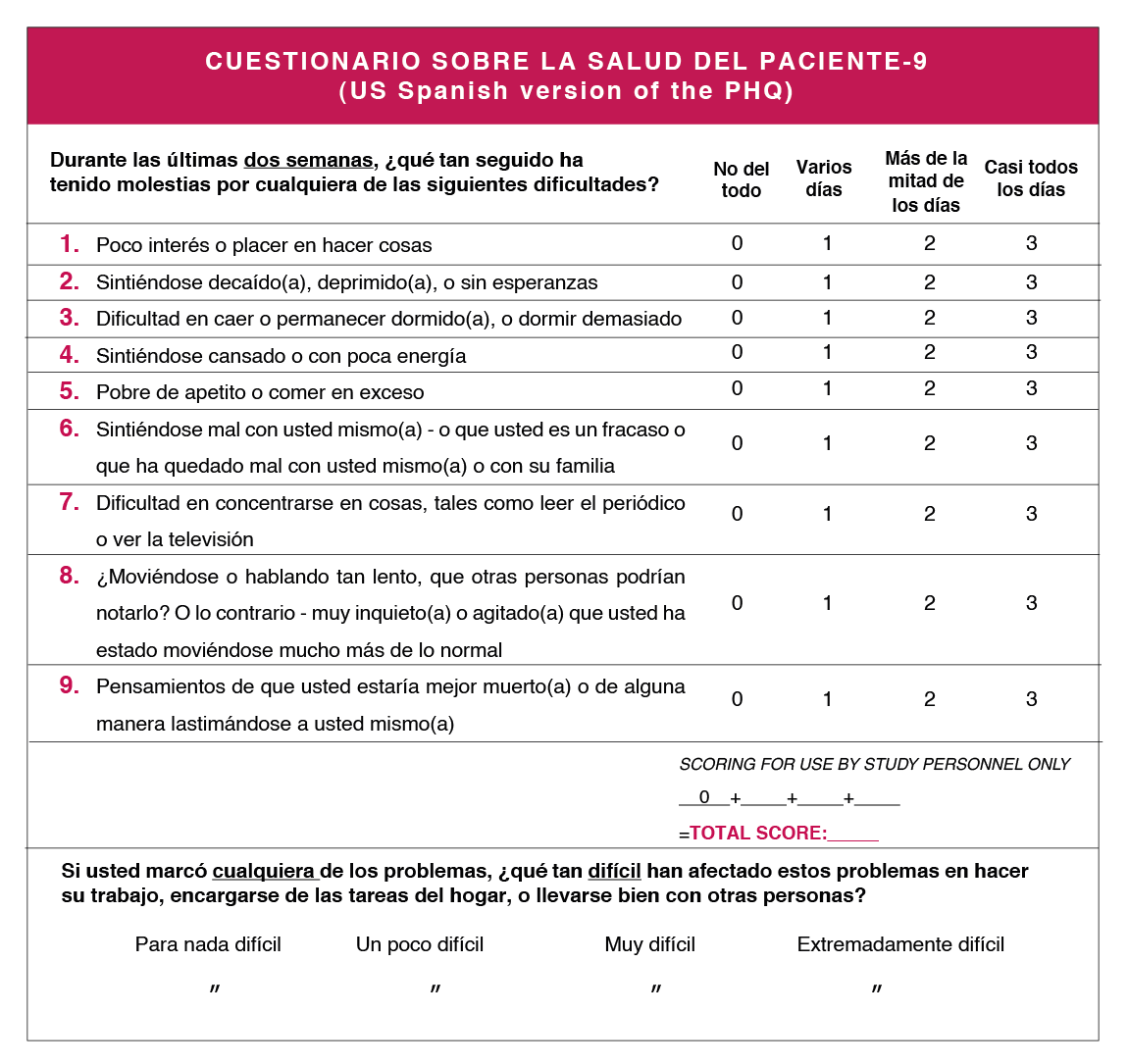

PHQ-9 |

Cuestionario sobre la salud del paciente – 9 |

RM |

Resonancia Magnética |

RR |

Riesgo Relativo |

SNC |

Sistema nervioso central |

TAR |

Tratamiento antirretroviral |

TCH |

D9-Tetrahidrocannabinol |

TNAV |

Trastornos neurocognitivos asociados al VIH |

TCS |

Trastornos por consumo de sustancias |

VHC |

Virus de la hepatitis C |

VIH |

Virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana tipo 1 |

4. ALTERACIONES PSICOLÓGICAS Y PSIQUIÁTRICAS

4.1. Aspectos psicológicos

4.2. Principales síndromes psicopatológicos

4.3. Alteraciones en las funciones fisiológicas

4.4. Trastornos por consumo de sustancias

4.5. Tratamiento de los trastornos psicopatológicos

4.6. Trastornos psiquiátricos en la población pediátrica

Aspectos psicológicos

Un aspecto importante para conseguir el bienestar de las personas que viven con el virus de inmunodeficiencia humana tipo I (VIH) y un control óptimo de la infección es identificar los procesos emocionales que pueden experimentar desde el momento del diagnóstico, así como los mecanismos, adaptativos o desadaptativos, que van a desarrollar para hacer frente a los estresores asociado al hecho de vivir con VIH.

Reacción ante la notificación del diagnóstico

Cuando una persona es diagnosticada de VIH puede experimentar una gran variedad de emociones como tristeza, miedo, rabia, ira, vergüenza, culpa o ansiedad1 y, sentir su pronóstico como incierto a pesar del buen pronóstico de la infección2. Estas emociones y reacciones pueden evolucionar de manera similar a como lo hacen los procesos de duelo, experimentando negación, enfado, negociación, depresión y finalmente aceptación3.

Durante la fase de negación la persona puede pensar que el diagnóstico es erróneo y/o resistirse a iniciar el tratamiento. En la fase de enfado pueden verse reacciones autodestructivas o evitativas como la alta actividad sexual no protegida o el consumo de alcohol y drogas. Durante la fase de negociación la persona puede experimentar fuertes sentimientos de arrepentimiento y culpa y, durante la fase de depresión desesperanza hacia el futuro y hacia sí mismo.

Adaptación frente a la enfermedad

Para adaptarse a vivir con una enfermedad crónica que requiere seguimiento médico continuado y un tratamiento diario, así como a otros cambios relacionados con el diagnóstico, la persona pone en marcha estrategias de afrontamiento. Estas estrategias son adaptativas, cuando permiten afrontar las demandas emocionales y desadaptativas cuando aumentan el nivel de malestar emocional4.

Las estrategias desadaptativas asociadas a mayores niveles de malestar y peor manejo terapéutico son: la evitación y negación; el aislamiento; y los pensamientos de carácter pasivo-rumitativo, los cuales son circulares sobre diversos aspectos de la enfermedad y no centrados en resolución de problemas5. Por el contrario, la persona que realiza un afrontamiento activo-conductual expresa sus emociones, demanda información o busca apoyo social, pone en marcha estrategias adaptativas.

La puesta en marcha de estrategias adaptativas o desadaptativas tras el diagnóstico dependerá de características psicológicas previas como rasgos de personalidad o recursos de regulación emocional, del nivel educativo o del apoyo social percibido, entre otros aspectos7. El desarrollo de estrategias desadaptativas se ha asociado con un peor control de la infección, por su papel en la amplificación del estrés8. Por este motivo es importante que el clínico responsable del VIH sea capaz de identificar la existencia de estas estrategias a tiempo y recomiende al paciente recibir atención psicológica.

Estigma

Una de las fuentes de estrés más relevantes para las personas con VIH se relaciona con el estigma social asociado a ser seropositivo. Este estigma tiene un alto impacto emocional cuando la persona incorpora la devaluación social en su propio sistema de valores9. El estigma que siente el paciente puede ser un estigma percibido, cuando anticipa (de forma real o imaginaria) como la sociedad se va a comportar frente a él/ella, o un autoestigma, cuando la propia persona expresa rechazo y repulsión por su condición de seropositivo10.

El estigma favorece que la persona responda frente a las emociones asociadas al diagnóstico con estrategias desadaptativas, presentando mayores niveles de distrés emocional, ansiedad y depresión11. Asimismo, el estigma se asocia con mayor discriminación, menor apoyo social, un acceso a los recursos sociosanitarios más reducido y, a una menor adherencia al tratamiento antirretroviral y peor control de la infección12.

Control de la infección y adherencia

Un aspecto clave para garantizar el bienestar de las personas con VIH es asegurar que siguen un control de la infección adecuado y toman su tratamiento de forma regular. Diversos estudios han considerado que la adherencia es un modelo de comportamiento psicosocial complejo y multifactorial, influenciado por diversas variables psicológicas13. Por ejemplo, el bajo apoyo social y las estrategias de afrontamiento desadaptativas tienen un efecto negativo a nivel psicológico (mayor ansiedad, depresión, malestar psicológico general), el cual predice una peor adherencia al tratamiento y control del VIH14. En la misma línea, en cuadros de depresión o duelo, la interrupción del TAR pueden estar asociada a sentimientos de culpa excesiva o realizarse como un modo de autolesión15.

Cuando una persona con VIH presenta un control deficiente de la infección y del TAR, se deben de analizar y abordar los aspectos psicológicos anteriormente mencionados así como aspectos como el uso de drogas o alcohol, la desconfianza sobre el TAR, la vergüenza asociada al estigma o la insatisfacción con la asistencia sanitaria. Igualmente, algunas otras estrategias como la simplificación del tratamiento, el uso de ayudas externas de recuerdo (alarmas, calendarios…) o recompensas por cumplimiento podrían ser de utilidad16.

Recomendaciones

- En todas las personas con VIH, especialmente tras el diagnóstico, sería recomendable realizar una valoración de su salud emocional, prestando especial atención a las estrategias de afrontamiento y al estigma (A-III).

- En aquellas personas en las que se detecten estrategias desadaptativas asociadas a cuadros de ansiedad o depresión se aconseja la derivación a un recurso de atención psicológica (A-III).

- En los pacientes con problemas de adherencia a la consulta y al TAR se recomienda realizar valoraciones psicológicas para identificar e intervenir sobre las variables emocionales asociadas a dichos problemas (B-III).

Principales síndromes psicopatológicos

La infección por VIH puede incrementar el riesgo de la enfermedad psiquiátricos y, a su vez, la enfermedad psiquiátrica es un factor de riesgo para la adquisición del VIH1718. Diferentes estudios han demostrado un aumento de la prevalencia de trastornos psicopatológicos en las personas con VIH en comparación con la población general19202122232425. El abordaje de estos trastornos requiere un abordaje multidisciplinar (medicina interna, psicología, psiquiatría, asistentes sociales, enfermería…) implicando, cuando sea posible a enfermería, como profesional de enlace. La valoración inicial y el seguimiento de los trastornos psicopatológicos en las personas con VIH deberá incluir27.

- Antecedentes familiares y personales de enfermedad mental y personales de consumo de tóxicos-drogas.

- Evaluación de la apariencia, del comportamiento, del pensamiento, del lenguaje, del juicio crítico, del estado de ansiedad y depresión, de la queja cognitiva (atención, memoria y funciones ejecutiva), de la motricidad y de la percepción

- Evaluación de la situación laboral, familiar y social.

4.2.1. Síndrome de ansiedad

Se estima que hasta un 47% de las personas con VIH padecerán ansiedad a lo largo de su vida2628. En estas personas, la ansiedad se ha con una merma significativa en la calidad de vida y con problemas en el manejo de la infección (retraso en el inicio del TAR, mala adherencia o pérdida del seguimiento)(26,29-31).

Diagnóstico

El cribado de la ansiedad se realiza mediante escalas que detectan síntomas ansiosos. En las personas con VIH, la más utilizada, es la escala de ansiedad y depresión hospitalaria (HADS) Figura 1. Una puntuación la subescala de ansiedad del HADS de al menos 8 puntos se considera sugestiva de trastorno de ansiedad32. La confirmación del diagnóstico la puede realizar directamente el clínico en la consulta, aplicando una entrevista semiestructurada como la entrevista neuropsiquiátrica internacional MINI33.

Tratamiento

El tratamiento inicial de los cuadros de ansiedad es la psicoterapia cognitivo- conductual, así como los grupos de apoyo, autoayuda y counselling. Cuando sea necesario asociar tratamiento farmacológico, los fármacos de elección serán los inhibidores selectivos de la recaptación de la serotonina (ISRS) a altas dosis34. Las benzodiacepinas (potentes y de vida media corta-media) se reservarán para cuadros de ansiedad aguda (1-2 semanas), en pacientes jóvenes.

4.2.2. Síndromes depresivos

Los síndromes depresivos en general y la depresión (5-20%) en particular son los trastornos psiquiátricos más prevalentes en las personas con VIH326. La prevalencia de depresión entre las personas con VIH es superior a la de la población general(20,35-42). y se ha asociado con peor control de la infección (retraso del inicio del TAR, mala adherencia o pérdida del seguimiento)(29,43-46) y con aumento de la morbi- mortalidad4748.

Diagnóstico

Para el cribado de la depresión se pueden utilizar escalas como el HADS32 aplicadas anual o bianualmente, en función del riesgo49. En personas con un HADS positivo, la confirmación del diagnóstico la puede realizar el médico de VIH, aplicando una entrevista semiestructurada como el MINI33 y descartando un origen orgánico de los síntomas depresivos (analítica completa con hormonas tiroides, folato y vitamina B12)26. Las pruebas de imagen cerebral no están indicadas de rutina y solo se indicarán cuando se sospeche organicidad. En todos los casos en que se identifique sintomatología depresiva habrá que realizar una evaluación del riesgo de suicidio. Para ello se recomienda utilizar la MINI o cualquier otra herramienta validada 33 En caso de que la valoración sea positiva habrá que evaluar que el paciente no reciba fármacos (como por ej. Efavirenz) asociados con un aumento del riesgo suicida y derivarlo para valoración urgente por un psiquiatra3738394041424344454647484950. Además del suicidio existen otras situaciones en las que se requerirá una valoración urgente por psiquiatría: heteroagresividad, repercusión funcional muy marcada, agitación o inhibición psicomotriz o síntomas psicóticos51.

Tratamiento

En la actualidad el modelo de manejo más aceptado para la depresión es el modelo de atención compartida entre salud mental y el médico responsable del paciente51. El tratamiento de la depresión incluye la psicoterapia525354 y los antidepresivos, siendo de elección los ISRS5556.

4.2.3. Síndrome maníaco

La prevalencia de síntomas maníacos en los pacientes con VIH es superior a la observada en la población general (8,1%)5758. La infección por VIH se ha relacionado con exacerbaciones de los síntomas maniacos y en la demencia VIH se han descrito cuadros de manía 596061626364. En relación con el TAR también se han evidenciado cuadros de manía con fármacos como Efavirenz5057. Desde el punto de vista terapéutico, la base del tratamiento de la manía secundaria serían los antipsicóticos y de la manía primaria los antipsicóticos combinados con eutimizantes como el litio o el ácido valproico. Otros fármacos potencialmente útiles, con escasa experiencia de uso en pacientes VIH, son la lamotrigina y la gabapentina556566.

4.2.4. Síndromes psicóticos

Los síndromes psicóticos son trastornos graves, que producen gran ansiedad al paciente, y que requieren un manejo especializado por psiquiatría6768. Como ocurre con la manía, la psicosis puede ser primaria o secundaria al VIH69707172. Los fármacos de elección son los antipsicóticos atípicos (clozapina, Risperidona, Olanzapina, quetiapina, amisulpiride, aripripazol o ziprasidona). El tratamiento se iniciará a dosis bajas y se mantendrá el menor tiempo posible, vigilando siempre la aparición de efectos adversos737475.

4.2.5. Trastornos de la personalidad

Entre las personas con VIH, la prevalencia de los trastornos de la personalidad puede alcanzar el 25%20 siendo los trastornos más comunes los del grupo B (el antisocial, el límite, el histriónico y el narcisista)68 Cuando se sospeche alguno de estos trastornos en la consulta de VIH, se deberá evaluar si existe riesgo de suicidio o autolesivo para posteriormente remitir al paciente, para recibir tratamiento (psicoterapia y farmacoterapia sintomática), a un especialista en salud mental6776.

Recomendaciones

- Se recomienda realizar despistaje de ansiedad y depresión, con escalas validadas como el HADS, en todas las personas con VIH en el momento del diagnóstico y a partir de ahí de forma anual o bianual (A-III).

- Cuando el resultado del despistaje de ansiedad o depresión sea positivo, el diagnóstico podría confirmarse directamente en la consulta, aplicando una entrevista semiestructurada como la MINI (B-II).

- Cuando se detecten síntomas depresivos (nuevos o un agravamiento de los ya existentes) se recomienda siempre evaluar ideación suicida y si se detecta, activar algún circuito de valoración urgente del paciente por parte de psiquiatría (A-III).

- El tratamiento inicial de los trastornos incidentales de ansiedad y de depresión que no cumplan criterios de complejidad se podrá realizar en la consulta de VIH, si se dispone de los medios y la preparación necesaria para ello (C-III).

- Cuando en una persona con VIH se detecte un trastorno maniaco o psicótico de reciente comienzo se recomienda valoración y tratamiento urgente por psiquiatría, así como descartar un origen orgánico del mismo (delirium, deterioro cognitivo, consumo de sustancias o fármacos como Efavirenz, enfermedades del sistema nervioso central (SNC)…) (A-III).

Alteraciones en las funciones fisiológicas

El diagnóstico y la vivencia de una enfermedad crónica como el VIH puede desencadenar respuestas emocionales adaptativas que se expresen mediante alteraciones en algunas funciones fisiológicas. De ellas, las más relevantes son las alteraciones del sueño, de la función sexual, del apetito, o la experimentación de fatiga. Cuando en una persona con VIH se detecten estas alteraciones se debe evaluar cual es la causa subyacente (depresión, el VIH, el TAR, comorbilidades…)77.

4.3.1. Trastornos del sueño

El insomnio es el trastorno del sueño más prevalente en personas con VIH)78. El insomnio es un fenómeno multidimensional en el que están implicados factores biológicos, psicológicos y psicosociales798081.

Diagnóstico

El despistaje del insomnio debería realizarse con frecuencia en el paciente con VIH, ya sea mediante una anamnesis dirigida que evalué la conciliación, la duración, la latencia y la calidad del sueño, así como el uso de hipnóticos o benzodiacepinas, o mediante una escala validada como el índice de calidad de sueño de Pittsburgh Figura 2. El diagnóstico del insomnio es clínico y se realiza por exclusión de otras alteraciones del sueño. El diagnóstico de insomnio se establece cuando se detectan problemas en la conciliación (>30 minutos), en el mantenimiento del sueño (despertares nocturnos de >30 minutos) o despertar precoz (>30 minutos antes de la hora deseada), que condicionan una alteración significativa en la funcionalidad diaria. La realización de pruebas complementarias como la polisomnografía solo estaría indicado en casos en los que se sospeche otro trastorno del sueño o en casos de insomnio refractarios al tratamiento.

Tratamiento

El tratamiento de elección del insomnio sería la psicoterapia (cognitivo-conductual) y la psicoeducación (revisión y corrección de las pautas de higiene del sueño)82. La psicoterapia para el insomnio puede ser proporcionada a través de varios métodos, tales como grupos terapéuticos, programas online, telefónicos o libros. Dentro de las herramientas disponibles, existe una específica para personas con VIH, la escuela del sueño online a la que se puede acceder a través del siguiente enlace: www. mejoratusueño.com. Cuando las técnicas de psicoterapia no sean efectivas o no estén disponibles, se recomienda ofrecer tratamiento farmacológico basado en evidencia83. Otra medida a contemplar en personas con VIH que reciben TAR es valorar si el paciente recibe algún fármaco que pueda inducir o agravar el insomnio como Efavirenz, Rilpivirina o los inhibidores de la integrasa84. Ver (Tabla 1).

4.3.2. Disfunción sexual

La disfunción sexual es un trastorno con una etiología mixta (psicológica y orgánica)8586 que, en el varón se expresa como disfunción eréctil, problemas de eyaculación, reducción del deseo sexual, funcionamiento orgásmico afectado y baja satisfacción sexual87 y en la mujer como disminución de placer y del deseo sexual13. Se estima que la disfunción sexual afecta con más frecuencia a las personas con VIH y que su prevalencia irá en aumento a medida que las personas con VIH envejezcan88, probablemente por una prevalencia de factores de riesgo como el tabaquismo, la obesidad, el sedentarismo, la hipertensión arterial (HTA), la diabetes mellitus (DM), la dislipemia la enfermedad cardiovascular 89.

Diagnóstico

La disfunción sexual requiere un abordaje multifactorial que cubra tanto factores psicológicos (imagen corporal, estigma o ansiedad-depresión asociada con la enfermedad y su trasmisión), como orgánicos: endocrinológicos (déficit de testosterona, hiperprolactinemia o hipertiroidismo), neurológicos (demencias, esclerosis múltiple), vasculares (enfermedad aterosclerótica) y locales (fractura de pene, fibrosis cavernosa…)9091. Otro factor para analizar sería el uso de algunos fármacos (antihipertensivos, antidepresivos, antipsicóticos, antiandrógenos o drogas recreacionales), que pueden justificar hasta el 25% de los casos 92.

Tratamiento

El tratamiento requiere la integración de abordajes psicológicos y médicos. Cuando se detecten disfunciones psicológicas de gravedad, se recomienda la derivación a especialistas en salud mental y sexología91. Respecto al tratamiento médico, la primera indicación sería disminuir o abandonar el consumo de tóxicos (alcohol, tabaco, drogas recreacionales) y modificar el tratamiento en caso de detectase el uso de fármacos que puedan causar disfunción sexual. La segunda, controlar los factores de riesgo vascular y disminuir el sedentarismo. Y la tercera, instaurar tratamiento farmacológico, preferiblemente con un inhibidor de la fosfodiesterasa-5 (sildenafilo, vardenafilo, tadalafilo o avanafilo) como fármaco de primera elección93, siempre ajustando la dosis (www.hiv-druginteracions.org) en función de la pauta de TAR. El uso de terapia sustitutiva con testosterona solo estaría indicado cuando se evidencie un hipogonadismo94. Otras opciones terapéuticas para valorar, en el varón, podrían ser la autoinyección de drogas en el pene, el uso de alprostadil intrauretral o el uso de dispositivos de aspiración en el pene; y, en la mujer, el uso de lubricantes vaginales, el tratamiento de la disfunción del suelo pélvico, el uso de cremas tópicas (1%) de testosterona (solo en mujeres postmenopáusicas) o el uso de fármacos no hormonales como la bremelanotida, la fibanserina o el Bupropion9596.

4.3.3. Trastornos del apetito

Las variaciones del apetito pueden tener un origen orgánico o psicológico. Dentro de las causas psicológicas los trastornos ansioso-depresivos se asocian con frecuencia a variaciones del apetito97. Cuando en la evaluación de una pérdida de apetito se detecten síntomas psicológicos, se recomienda que el paciente sea valorado por un profesional de salud mental.

4.3.4. Fatiga

La fatiga es un síntoma multifactorial, muy comúnmente referido por las personas con VIH98.La fatiga se ha asociado con multitud de factores de riesgo: el VIH o el TAR, el insomnio, la ansiedad, la depresión o el estrés postraumático…889899.

La terapia cognitivo-conductual ha demostrado ser de utilidad en el tratamiento de la fatiga en personas con VIH. Por el momento no existe ningún tratamiento que haya demostrado efectividad reduciendo la fatiga98100.

Recomendaciones

- El despistaje, mediante la anamnesis, de los trastornos del sueño debería realizarse en cada visita médica del paciente (A-III) y de forma anual o bianual mediante escalas como el índice de calidad del sueño de Pittsburg (B-II).

- El tratamiento inicial de los trastornos del sueño se basa en la revisión del cumplimiento de las pautas de higiene del sueño (A-III) y en las técnicas de terapia cognitivo-conductual (A-I).

- Se recomienda evitar hipnóticos y benzodiacepinas en el tratamiento del insomnio crónico. En el agudo, solo serán de elección en cuadros que no responda a las medidas no farmacológicas (C-III).

- En los cuadros de insomnio crónico secundario a trastornos emocionales pueden ser de utilidad los antidepresivos sedantes como la Mirtazapina y la trazodona (C-III).

- Se recomienda realizar despistaje de la disfunción sexual, mediante la anamnesis, de forma anual (A-III).

- El tratamiento de elección de la disfunción sexual son los inhibidores de la fosfodiesterasa-5, ajustados en función de la pauta de TAR (B-I).

- Ante cualquier variación significativa del apetito se recomienda, entre otras medidas, el despistaje de trastornos ansioso-depresivos (A-II).

- La terapia congnitivo-conductual podría ser de utilidad en el manejo de la fatiga(B-II).

Trastornos por consumo de sustancias

En las personas con VIH es muy frecuente identificar el consumo de sustancias psicoactivas. En la mayoría de los casos, estos consumos son ocasionales y esporádicos y no se asocian con problemas de salud. Solo cuando los consumos, inicialmente voluntarios, se vuelven problemáticos (se intensifican, escapan al control del individuo y perjudican la salud, en un contexto psico-bio-social, durante un periodo de tiempo significativo) se puede establecer un diagnóstico de trastorno por consumo de sustancias (TCS).

Los TCS son frecuentes en las personas con VIH101102 En esta población, el diagnóstico precoz y el tratamiento de los TCS es particularmente importante103 dado que, su presencia se ha asociado con un peor control de la infección104105106107, con más conductas de riesgo para la transmisión del VIH108, con más sintomatología asociada al VIH109110, con mayores tasas de hospitalización111, con peor calidad de vida112 y con una menor supervivencia113. Los trastornos por consumo de sustancias más frecuentes en las personas con VIH son:

Alcohol

La prevalencia del consumo excesivo de alcohol en las personas con VIH casi dobla a la de la población general114. Este tipo de consumo se ha relacionado con una mala adherencia al TAR, además de afectar las respuestas del sistema immune115116. La intoxicación por alcohol suele tener un efecto inmunosupresor mientras el consumo crónico podría ser inmunoactivador y causar inflamación crónica y estrés oxidativo115. También se asocia a un mayor riesgo de progresión de la enfermedad y un aumento del riesgo de transmisión117118119120. El consumo de alcohol en las personas con VIH aumenta el riesgo de enfermedades cardiovasculares121 en un rango del 37% al 78% 122 y de cáncer, especialmente hepatocarcinoma123 También se ha asociado a disfunción neurocognitiva124125. Sin embargo, aunque no graves, algunos estudios han descrito interacciones 126 leves del alcohol con Abacavir127, Efavirenz128 Maraviroc129o Ritonavir128.

Nicotina

La prevalencia de tabaquismo entre las personas con VIH es 2-3 veces superior a la de la población general130131y es más difícil que dejen de fumar132. El tabaquismo en las personas con VIH se asocia con un aumento en la incidencia de enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica, cáncer de pulmón y enfermedades cardiovasculares y en la tasa de mortalidad133 que, se reduce al abandonar el hábito tabáquico134135. De igual forma, las personas que dejan de fumar mejoran su calidad de vida136137.

Cannabis

Los principales efectos adversos del cannabis son taquicardia, agitación, náuseas, trastornos cognitivos y trastornos psiquiátricos, como la psicosis o la paranoia138. El consumo de cannabis con fines medicinales o recreativos en las personas con VIH se estima entre 15-40%139140141142. Aunque la influencia o no del cannabis sobre el control del VIH es controvertida143144145, sus efectos secundarios, al menos de momento, desaconsejan su uso.

Cocaína

Se estima que, alrededor de ¼ parte de las personas con VIH en nuestro medio consumen cocaína146. El impacto de este consumo repercute de forma negativa sobre el control y la morbilidad relacionada con la infección y favorece conductas sexuales de riesgo20,147148149. Las principales complicaciones de la cocaína son problemas cardiovasculares, pulmonares, deterioro cognitivo, daño hepático, trastornos obstétricos y trastornos psiquiátricos (irritación, ataques de pánico, paranoia, juicio deteriorado, delirios, alteración del sueño)150.

Opiáceos

Los opiáceos son sustancias que actúan sobre los receptores endógenos opioides (mu, delta, kappa) produciendo analgesia y alteraciones del estado de ánimo. En las últimas dos décadas, el uso de opioides como la oxicodona o el fentanilo se ha asociado con un importante problema de adicción a estas sustancias151 que en algunos casos a favorecido un aumento de la trasmisión del VIH152153.

Estimulantes

El prototipo de estimulante es la 3,4-metilendioxi-metanfetamina (MDMA), un derivado anfetamínico de consumo oral (comprimidos o cristales pulverizados) con efecto empatógeno que favorece el acercamiento interpersonal. Los efectos adversos más relevantes del MDMA son: bruxismo, nistagmo, sudoración profusa, distorsiones visuales, hipertermia, hiponatrimia grave, rabdomiolisis, insuficiencia renal, convulsiones, hepatopatía156y neurotoxicidad157. En los últimos años han aparecido alternativas al MDMA (4-bromo-2,5-dimetoxifeniletilamina) con un perfil mixto (estimulante y psicodélico) y connotaciones eróticas158.

Alucinógenos

Los alucinógenos son sustancias con capacidad para alterar la conciencia, favoreciendo modificaciones en el ánimo, en los procesos de pensamiento y en la percepción del entorno y del yo159 Algunas de las sustancias alucinógenas más utilizadas son la dietilamida del ácido lisérgico, o LSD, la mescalina y la ketamina160. El principal riesgo de estas sustancias radica en la práctica de actividades peligrosas bajo su influencia (como escalar, intentar nadar, etc.)161.

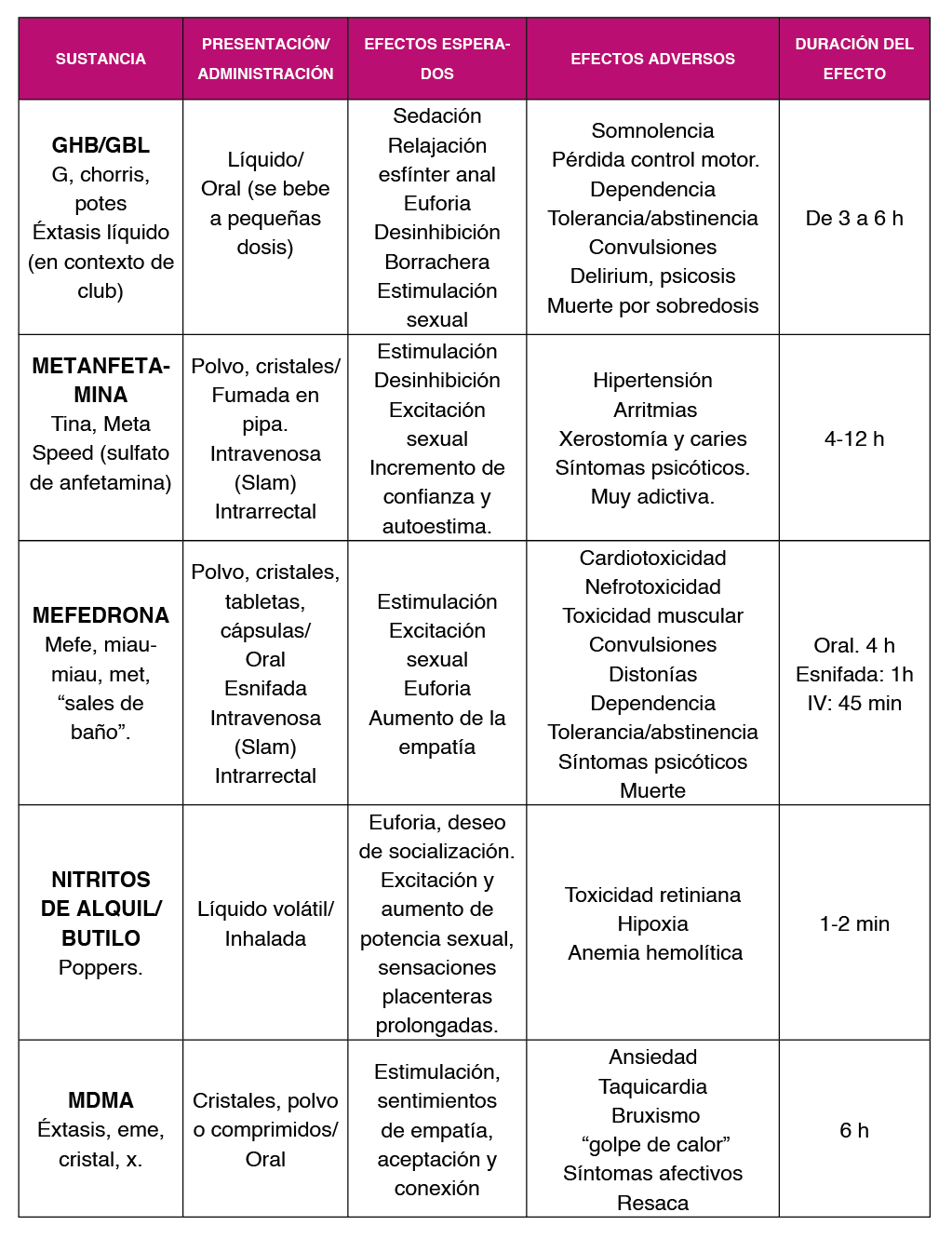

Sustancias asociadas a las relaciones sexuales – “chemsex”

El chemsex hace referencia al uso intencionado de sustancias para potenciar las relaciones sexuales, por un largo periodo de tiempo, generalmente en el colectivo de hombres que tienen sexo con hombres888990. Las sustancias más utilizadas en la práctica del chemsex con sus principales características se incluyen en la Tabla 2 y Tabla 3.

En general, la práctica de chemsex suele ser una actividad recreativa y ocasional que, en personas vulnerables, con el tiempo se trasforma en problemática. En estos casos de chemsex problemático, es frecuente identificar TCS asociados con alguna sustancia, conductas compulsivas conductuales (sexo compulsivo) y otras adicciones comportamentales (adicción a las aplicaciones de contactos).

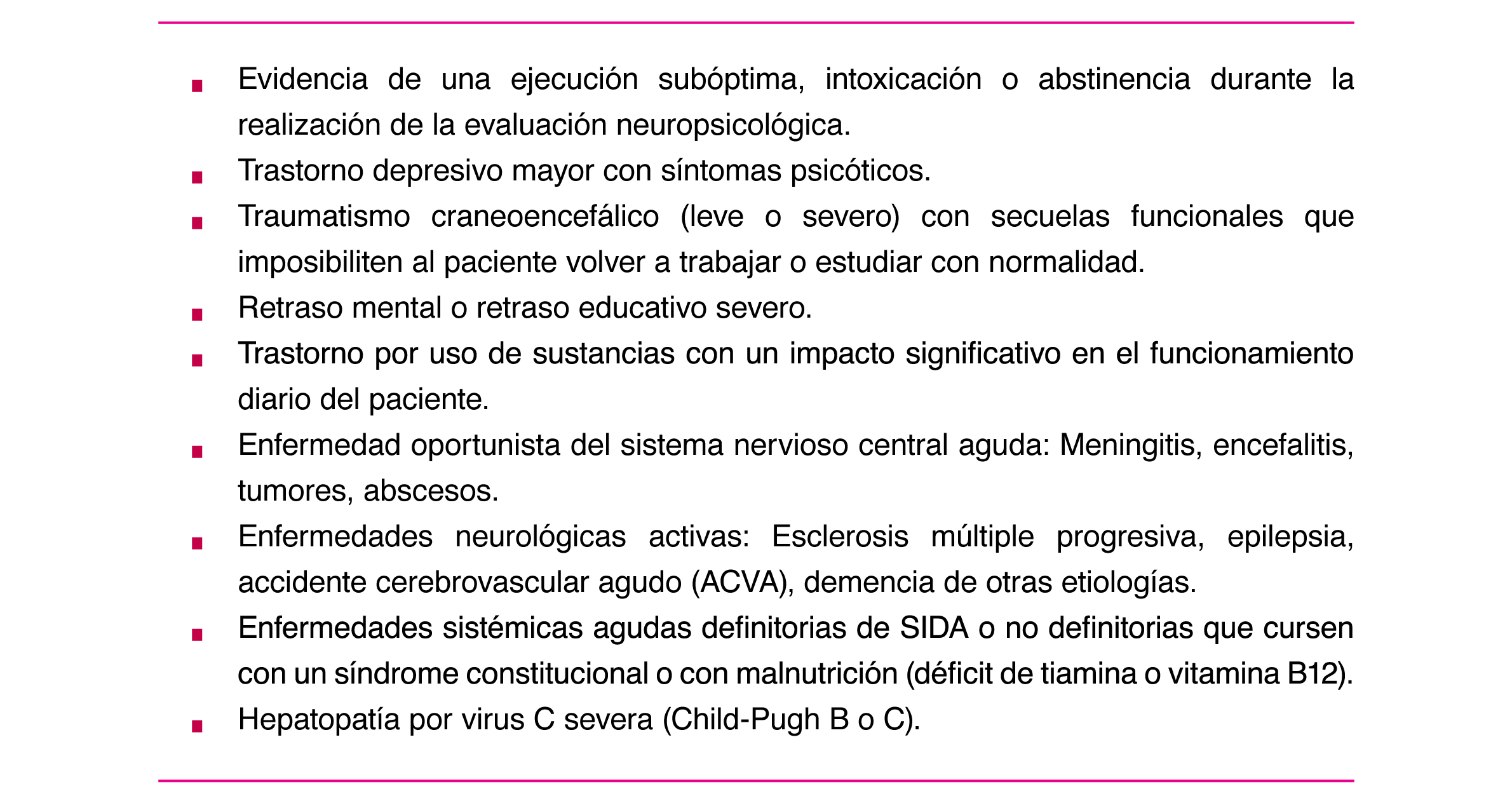

4.4.1. Diagnóstico

La evaluación del consumo de sustancias debería estar integrada en la anamnesis realizada al paciente con VIH en cada visita. Cuando se detecte el consumo de alguna sustancia psicoactiva, habrá que valorar: su cuantía, su frecuencia, su perfil de consumo, su vía de administración, la predisposición del paciente a abandonar o reducir el consumo, la existencia de complicaciones y de vulnerabilidades (situación social y personal). En la práctica del chemsex, habrá que explorar también el riesgo asociado con las relaciones sexuales (número de parejas, tipo de relaciones sexuales, uso de preservativo o número de infecciones de transmisión sexual (ITS)). Durante la exploración habrá que evaluar la higiene personal, la pérdida o ganancia de peso, los signos secundarios a la venopunción o a la inhalación de drogas (atrofia de la mucosa nasal o perforación del tabique nasal), la pérdida de piezas dentarias y posibles signos de intoxicación o abstinencia. La realización de pruebas de detección de tóxicos no se recomienda de rutina, aunque puede ser de utilidad. Como alternativa a la anamnesis dirigida o de forma complementaria a la misma, existen escalas validadas como la DUDIT (Drug Use Disorders Identification Test) (162 o la AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) 163 que pueden ser de utilidad en el despistaje de los TCS Figura 3, Figura 4 y Figura 5. El uso de estas escalas podría ser de utilidad en la valoración inicial tras el diagnóstico de VIH y en el seguimiento de forma anual o bianual, en función del perfil de riesgo del paciente. En aquellas personas con un despistaje positivo, La confirmación del diagnóstico la puede realizar directamente el clínico en la consulta, aplicando una entrevista semiestructurada como la entrevista neuropsiquiátrica internacional MINI 33.

4.4.2. Tratamiento

El manejo del consumo de sustancias deberá realizarse desde la consulta de VIH. El objetivo será minimizar los riesgos asociados al consumo: asegurar la adherencia al TAR, evitar las interacciones farmacológicas, evitar que se compartan las jeringuillas, las pipas o los dispositivos para esnifar... En el caso del chemsex, habrá que explorar y minimizar el riesgo de ITS (uso de la PrEP, del preservativo, screening frecuente de ITS y formación en reducción de riesgos, cuando el paciente opte por prácticas sexuales no protegidas), así como establecer circuitos de derivación específicos para el abordaje global de la sexualidad y el consumo. Cuando el consumo empiece a ser problemático o exista un TCS, el paciente debería ser remitido a un centro especializado en el tratamiento de adicciones para su tratamiento. La base del tratamiento para muchas adicciones (cannabis, cocaína, MDMA) que no cuentan con ningún tratamiento farmacológico específico es la psicoeducación y/o la psicoterapia164165. Desde el punto de vista farmacológico disponemos de tratamiento efectivo frente a la adicción por nicotina (por orden de eficacia: vareniclina166167 el Bupropion166 y terapia de sustitución con nicotina168) y por opiáceos (terapia de sustitución con metadona169). Cuando la adicción se asocie con estigma social, como ocurre por ejemplo con los opiáceos, se recomienda integrar el tratamiento de la adicción y de la infección VIH170171172. El papel del médico de VIH en el tratamiento de los TCS comprenderá la prevención y el manejo de complicaciones médicas, como las sobredosis, las intoxicaciones y las infecciones173174 Estas complicaciones son más frecuentes cuando se consume por vía endovenosa o se practica el policonsumo175.

Recomendaciones

- Se recomienda valorar el consumo de sustancias con regularidad, ya sea mediante la anamnesis y/o utilizando escalas validadas como el DUDIT o el AUDIT (A-III).

- En las personas con VIH que consumen sustancias psicoactivas sin evidencia de TCS, se recomienda la implementación de estrategias de minimización de riesgos (B-III).

- El tratamiento de los TCS debe ser

- El único tratamiento efectivo para los TCS por cannabis, cocaína y MDMA es la psicoterapia y/o psicoeducación (B-II).

- En las personas con VIH el tratamiento de elección para la deshabituación tabáquica es la vareniclina (B-II).

Tratamiento de los trastornos psicopatológicos

En la población general, el primer eslabón en el abordaje de los problemas de salud mental recae en los médicos de atención primaria. Con frecuencia, las personas con VIH utilizan al especialista en VIH como su médico de primaria. Cuando esto ocurre, el especialista en VIH tendrá que asumir las funciones de diagnóstico y tratamiento inicial de los trastornos mentales de sus pacientes, así como la coordinación con los servicios de salud mental176177178. El abordaje recomendado en estos casos se realizará en coordinación y colaboración con los profesionales en salud mental y deberá incluir176177178179180.

- Educación sanitaria sobre VIH y salud

- Educación sobre conductas de riesgo (consumo de sustancias).

- Intervenciones encaminadas a la minimización de

- Detección precoz de la enfermedad mental y, en función del tipo de trastorno, su tratamiento inicial o su derivación a salud

- Promoción de la continuidad de cuidados y de la adherencia al plan terapéutico.

4.5.1. Tratamiento psicofarmacológico

Respecto al tratamiento psicofarmacológico, el especialista en VIH debería estar familiarizado con los efectos adversos y las interacciones de los fármacos que con mayor frecuencia reciben las personas con VIH. Igualmente debería conocer y manejar el tratamiento de primera línea de aquellos trastornos que no requieran para su tratamiento inicial de un especialista en salud mental. A continuación, se describe el manejo de los principales grupos de psicofármacos en las personas con VIH.

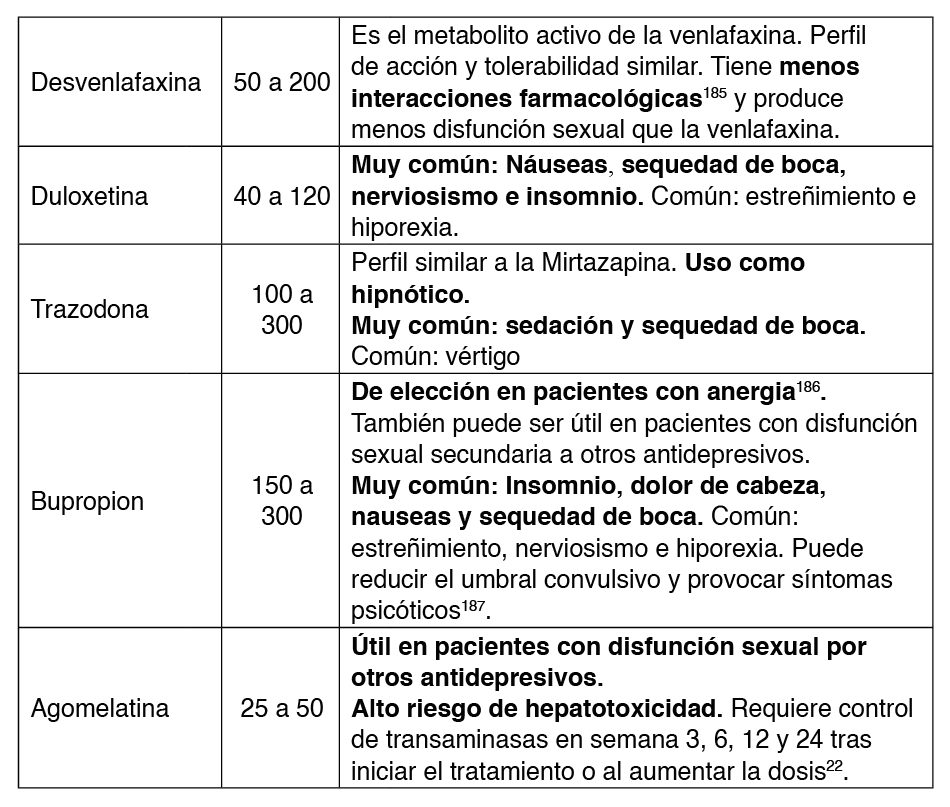

4.5.1.1. Antidepresivos

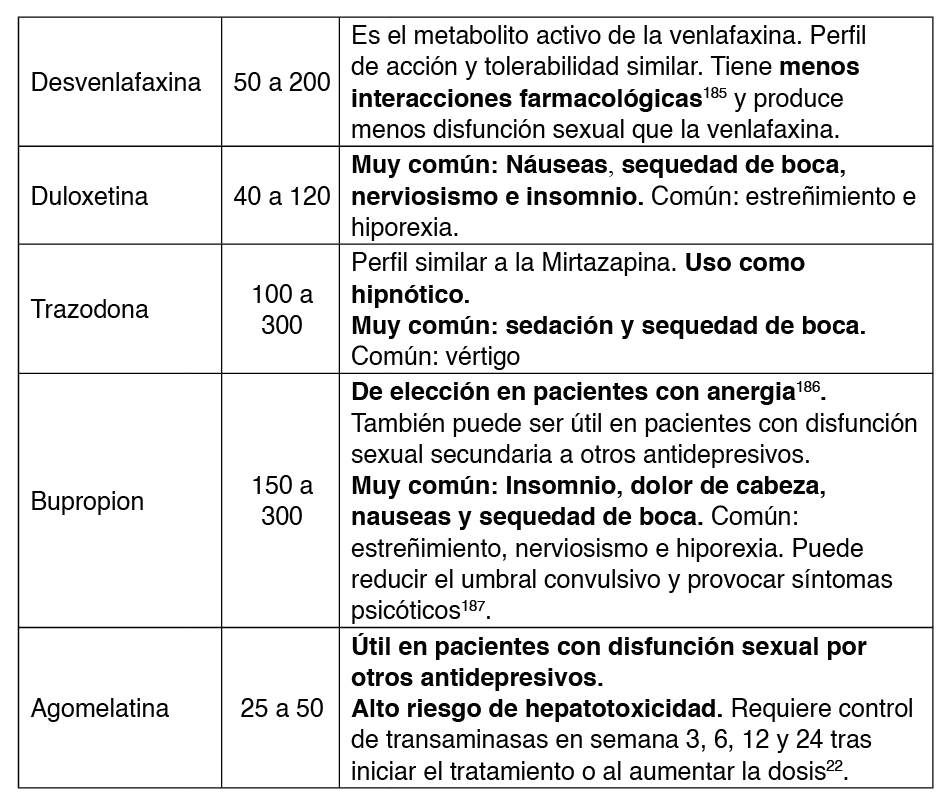

Los antidepresivos son el tratamiento de elección de los trastornos depresivos y de los trastornos de ansiedad Tabla 4 y Tabla 5. En las personas con VIH, los antidepresivos tienen una buena tolerabilidad y su eficacia en el control de los síntomas de ansiedad y depresión es superior a la del placebo181.

Fármacos de elección

Por su perfil de interacciones los antidepresivos de elección en las personas con VIH serían los ISRS y dentro de ellos, Citalopram y Escitalopram55. En pacientes con comorbilidades el fármaco de elección puede variar. En la Tabla 6 se recoge el fármaco de elección en presencia de algunas comorbilidades comunes en las personas con VIH.

Modelo de tratamiento de la depresión

En las personas con VIH se recomienda un modelo de atención como el de Adams et al, basado en la monitorización188 según los siguientes principios:

- El tratamiento debe buscar la remisión y no la respuesta. Se recomienda ajustar el tratamiento hasta que se haya logrado una recuperación completa sin síntomas depresivos

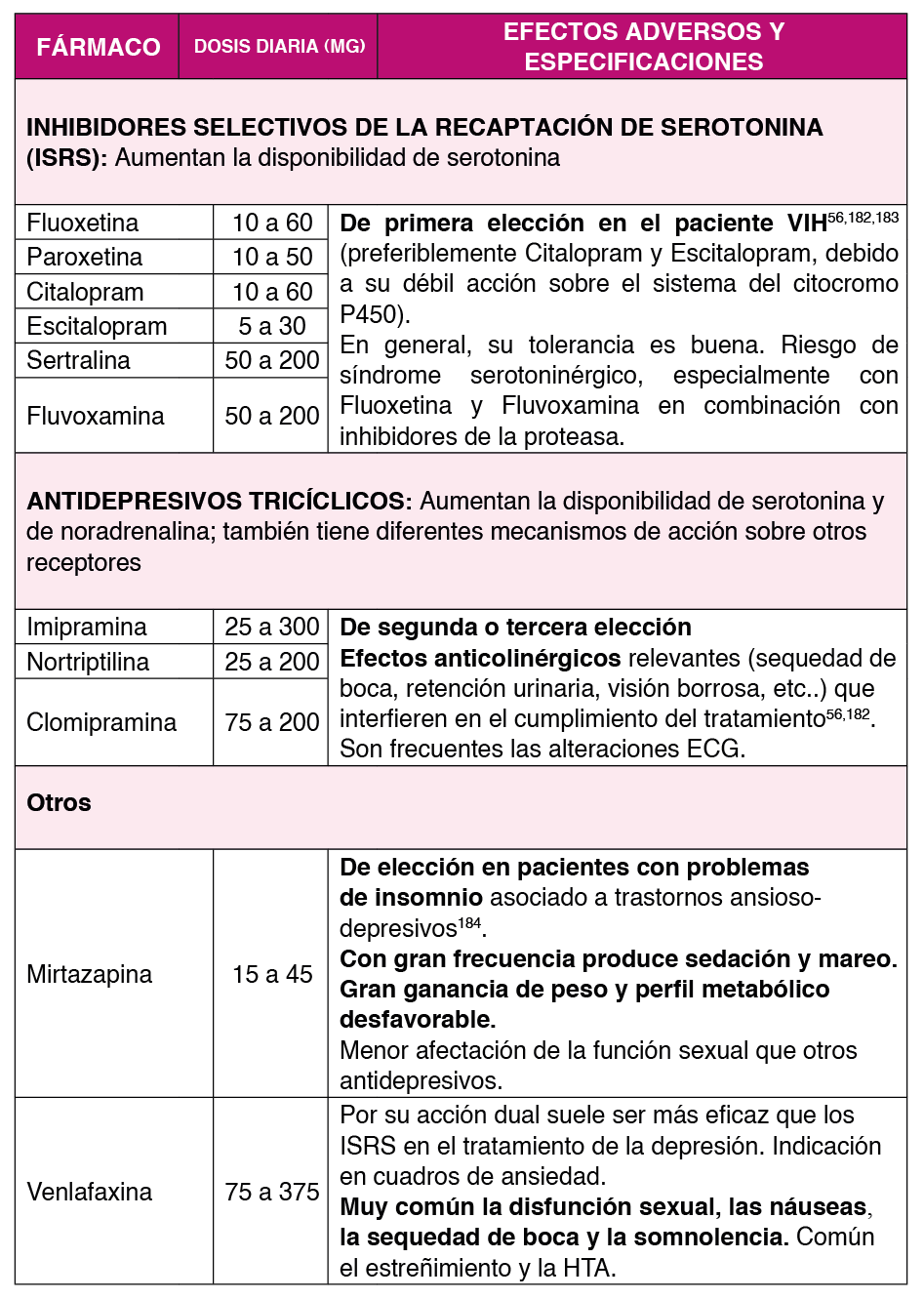

- Evaluación sistemática de los síntomas En pacientes diagnosticados de depresión, las decisiones terapéuticas deben basarse en medidas cuantitativas validadas y no en la impresión clínica. Para ello se recomienda el uso de instrumentos validados como el cuestionario sobre la salud del paciente – 9 (PHQ-9) 189.

- Monitorización frecuente de los efectos La principal causa de interrupción del tratamiento antidepresivo es la aparición de efectos adversos indeseados (disminución de la libido o aumento de peso). La monitorización frecuente y el tratamiento precoz de los efectos adversos disminuye el riesgo de interrupción del tratamiento y aumenta la adherencia.

- Inicio con la mínima dosis Para un mejor control de los efectos adversos y evitar la discontinuación del tratamiento, se recomienda el inicio del tratamiento antidepresivo con la dosis eficaz más baja.

- Aumentar la dosis de forma progresiva hasta alcanzar la remisión. La respuesta al tratamiento debe evaluarse cada 4 semanas y si se observa mejoría insuficiente, la dosis debe aumentarse hasta que se logre la remisión, hasta que los efectos adversos sean intolerables o hasta que se haya alcanzado la dosis máxima.

- Asegurar un tratamiento adecuado antes de cambiar o remitir al Mientras los efectos adversos sean tolerables, antes de considerar el cambio del tratamiento o remitir al paciente a una unidad especializada, el paciente debe recibir el tratamiento durante al menos 12 semanas, al menos 4 de ellas a dosis moderadas o altas).

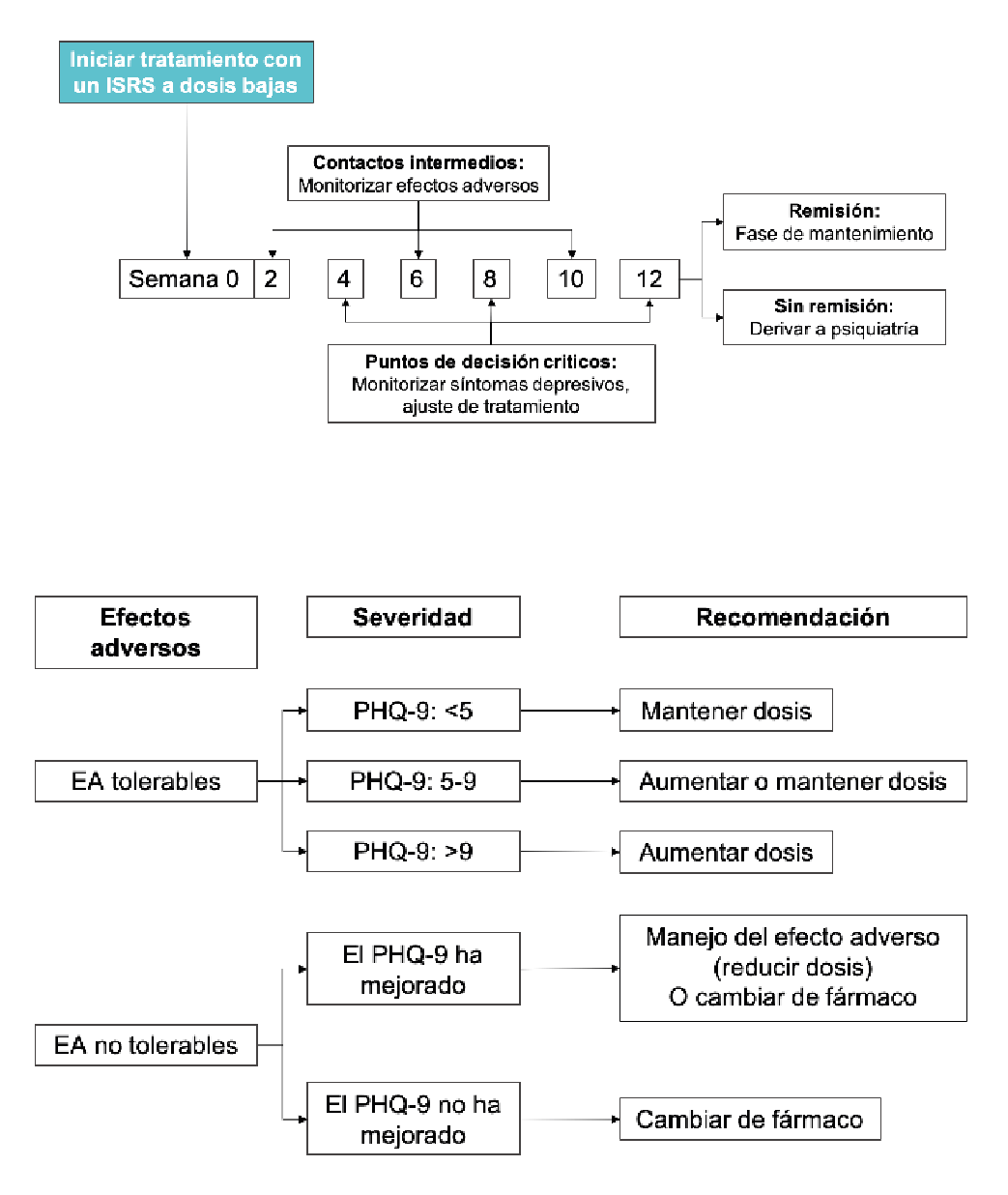

En la Figura 6 se recoge un algoritmo para que el especialista en VIH pueda iniciar el tratamiento de la depresión en la consulta de VIH basado en el modelo de Adams et al188). De forma esquemática el algoritmo propone iniciar el tratamiento con un ISRS a dosis bajas, monitorizando la aparición de efectos adversos en las semanas 2, 6 y 10 del seguimiento y la eficacia en las semanas 4, 8 y 12. La monitorización de efectos adversos puede ser telemática (médico o enfermera). Para evaluar la eficacia se utilizaría la puntuación obtenida por el paciente en el PHQ-9 Figura 7. Como refleja el algoritmo, la indicación de mantener o cambiar la dosis o el tratamiento se basarían en la presencia de efectos adversos y en el resultado del PHQ-9. Si a las 12 semanas desde el inicio del tratamiento no se ha conseguido la remisión de los síntomas depresivos se recomienda derivar al paciente a salud mental. Si se ha conseguido, se recomienda mantener el tratamiento durante 6 meses tras la remisión.

Modelo de tratamiento de la ansiedad

El modelo de tratamiento para la ansiedad es similar al propuesto para la depresión, con la salvedad de que no siempre es posible alcanzar la remisión total y que el mantenimiento del fármaco tras alcanzar la respuesta será de 12 meses en lugar de 6. Respecto a la herramienta para el control sintomático, se podría utilizar la subescala de ansiedad del HADS.

4.5.1.2. Ansiolíticos y otros fármacos hipnótico-sedantes

Benzodiacepinas

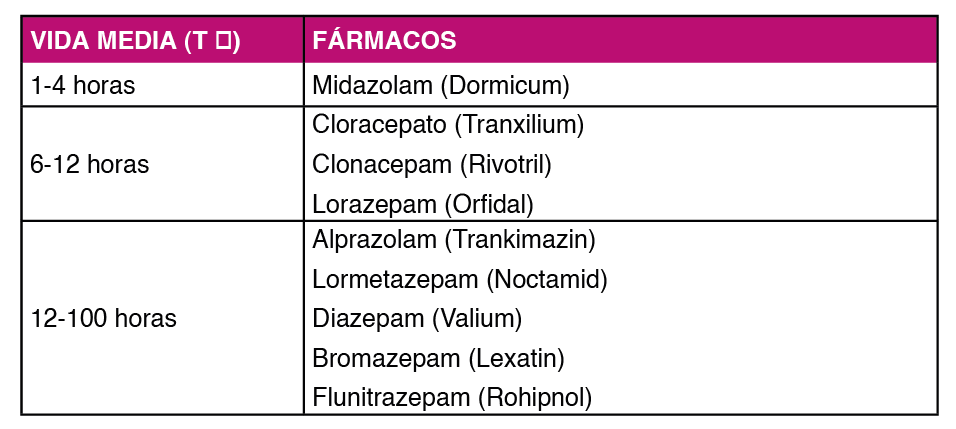

Las benzodiacepinas son fármacos que por su efecto ansiolítico potente están indicados en el tratamiento agudo de la ansiedad. Su uso se recomienda en periodos cortos (4 semanas) ya que así se reduce el riesgo de tolerancia o adicción y se consigue la máxima eficacia79 Es referible evitar este tipo de fármacos en pacientes con dependencia del alcohol y en aquellos que tienen antecedentes de abuso de sustancias190. Igualmente se desaconseja su uso en personas de edad avanzada porque aumentan el riesgo de deterioro cognitivo y de delirium.

Por su vida media, las benzodiacepinas se clasifican en vida media larga y vida media corta o media Tabla 7. Las primeras tienen la ventaja de su dosificación como monodosis nocturna y de presentar un síndrome de retirada menor. Por el contrario, tienen una mayor influencia en la actividad psicomotora y producen sedación diurna. En los pacientes con VIH se recomienda el uso de benzodiacepinas de vida media corta o media, sin metabolitos activos, siendo de elección el Lorazepam.

Gabapentina y Pregabalina

Son antiepilépticos que se utilizan como ansiolíticos. Pregabalina tiene indicación para el trastorno de ansiedad. Son fármacos con riesgo escaso de interacción farmacológica, ya que no se metabolizan. Algunos estudios indican su utilidad en pacientes con VIH con dolor neuropático191.

Zolpidem y Zopiclona

Son fármacos que se usan como hipnóticos en los trastornos del sueño.

4.5.1.2. Antipsicóticos y eutimizantes

Los antipsicóticos y los eutimizantes son fármacos de manejo complejo por su perfil de indicación y sobre todo de efectos adversos, por lo que se recomienda que su prescripción la realice un especialista en psiquiatría. Los antipsicóticos pueden ser utilizados por el especialista en VIH para tratar cuadros de delirium. En el paciente con VIH por su perfil de interacciones, el antipsicótico de elección serían la Paliperidona.

4.5.1.3. Tratamientos alternativos

Con frecuencia las personas con VIH toman sustancias llamadas “naturales” para tratar síntomas como el insomnio, la depresión, la fatiga, la ansiedad o las quejas cognitivas. Alguna de estas sustancias como el hypericum perforatum (hierba de san Juan) tienen importantes interacciones medicamentosas que desaconsejan su uso con el TAR193.

4.5.1.4. Interacciones entre los psicofármacos y el TAR

En las personas con VIH que reciben TAR se recomienda que la elección del tratamiento psicofarmacológico tenga en cuenta el perfil de efectos adversos y de interacciones del TAR177. Para ello se puede consultar el Documento de consenso de GeSIDA sobre el TAR en adultos con VIH194. El tratamiento se debe iniciar con la posología más cómoda posible, a dosis bajas, y el incremento de dosis debe ser lento.

La evaluación de las interacciones entre el TAR y los psicofármacos es compleja porque en la mayoría de los casos estas interacciones se basan en modelos teóricos y no en estudios farmacocinéticos, los cuales además no suelen tener en cuenta que las interacciones múltiples. Antes de prescribir un psicofármaco se recomienda la consulta de interacciones farmacológicas en alguno de estos recursos: www.hiv- druginteractions.org o www.interaccionesvih.com.

Recomendaciones

- Antes del inicio de un tratamiento psicofarmacológico se recomienda evaluar los posibles efectos adversos comunes y las interacciones con el TAR y con el resto de medicación, prescrita y no prescrita (productos naturales, medicinas alternativas, drogas), que toma el paciente (A-III).

- Se recomienda que el inicio de cualquier psicofármaco sea a dosis bajas y el incremento de dosis lento (A-III).

- En las personas con VIH, se recomienda aplicar el modelo de atención basada en la monitorización al tratamiento psicofarmacológico de la depresión (A-III).

- Los fármacos de elección en los trastornos de ansiedad y depresión en las personas con VIH serán los ISRS (A-II).

- Por su bajo riesgo de efectos extrapiramidales, su buen perfil metabólico y la ausencia de interacciones significativas con el TAR, el antipsicótico de elección en las personas con VIH será la Paliperidona (A-III).

- En la consulta de VIH, el uso de benzodiacepinas debería limitarse al tratamiento de cuadros agudos de ansiedad o insomnio (1-4 semanas), siendo la benzodiacepina de elección el lorazepam (C-III).

- Se recomienda limitar el uso de benzodiacepinas en las personas con VIH, especialmente en aquellas de edad avanzada o con antecedentes de trastornos por consumo de alcohol o sustancias (C-II).

4.5.2. Intervenciones psicológicas

El objetivo de las intervenciones psicológicas recomendadas en las personas con VIH es aliviar el sufrimiento relacionado con el diagnóstico de VIH y mejorar su calidad de vida195. Las intervenciones psicológicas en las personas con VIH serían:

El counselling al diagnóstico

El counselling o ayuda psicológica es una intervención que puede realizar cualquier profesional sanitario, formado previamente, orientada a ayudar al paciente a adaptarse a acontecimientos vitales estresantes196197. En las personas con VIH, las intervenciones de counselling pueden ayudar al paciente a afrontar el diagnóstico y a adaptarse a los acontecimientos vitales estresantes asociados con su condición de seropositivo196197 El counselling durante el diagnóstico debe realizarse de forma individual y confidencial, dedicando el tiempo necesario para evaluar el estado emocional y permitir al paciente exponer sus inquietudes y temores198 Los objetivos de esta intervención deben ser:

- Comunicar los resultados de forma clara, precisa y asertiva

- Escuchar al paciente de manera activa

- Asesorar en estrategias básicas de afrontamiento ante la situación estresante para reducir la ansiedad

- Aportar información precisa sobre la enfermedad (síntomas, evolución, opciones de tratamiento…)

- Romper estereotipos sociales y falsas creencias

- Recordar la alta eficacia del tratamiento

- Normalizar posibles intervenciones psicosociales posteriores

- Abordar dudas, dificultades, temores y momento para la comunicación de la seropositividad a su familia o pareja

Es importante resaltar la importancia del profesional sanitario en el apoyo emocional a las familias, para detectar y evitar los procesos de culpabilización por parte de los familiares e implicarles en un estilo de vida más saludable que debe proponerse el paciente199. En la valoración del paciente con VIH hay que tener en cuenta síntomas e indicios clínicos200 cuya presencia haría necesaria la derivación a Salud Mental para una evaluación e intervención especializada:

- Comorbilidad psiquiátrica

- Ideación o verbalización suicida

- Alteraciones anímicas y afectivas recurrentes

- Sentimientos de indefensión y desesperanza

- Conductas desadaptativas con escasa capacidad de afrontamiento

- Síntomas de ansiedad o depresión persistentes compatibles con un trastorno adaptativo de curso crónico

- Rasgos patológicos y desadaptativos de la personalidad

Intervenciones psicoeducativas

Las intervenciones psicoeducativas son estrategias educativas o formativas cuyo objetivo es desarrollar habilidades y recursos propios que permitan afrontar mejor los trastornos mentales, evitar las recaídas y mejorar la calidad de vida. En las personas con VIH, se ha evaluado con resultados inconsistentes, la utilidad de programas de intervención que aborden el malestar emocional, la indefensión, la percepción de falta de control y que promuevan el apoyo social, con el objetivo de mejorar la adherencia y las conductas de autocuidado201202.

Intervenciones psicoterapéuticas

Las intervenciones psicoterapéuticas son tratamientos, individuales, grupales o familiares, de naturaleza psicológica cuyo objetivo es lograr cambios en el comportamiento que mejoren la salud física y psíquica. Estas terapias pueden ser más eficaces para tratar algunos trastornos, como los depresivos leve-moderados, que las intervenciones farmacológicas203204. En las personas con VIH estas terapias van a favorecer una evolución positiva de la infección. La mayoría de los estudios realizados en personas con VIH han tenido un abordaje grupal, siendo escasos los que han evaluado estrategias individuales205206207208.

Terapias grupales

Las terapias grupales son más coste-efectivas que las individuales, por lo que, en un entorno de alta presión asistencial como el nuestro, permiten acceder a ellas a un mayor número de usuarios. Estas terapias han demostrado, al menos en el corto plazo, su utilidad en el manejo del estrés, la depresión, la ansiedad, el funcionamiento psicológico global, el soporte social y la calidad de vida206. Dentro de este grupo de terapias, las intervenciones basadas en mindfulness constituyen otra aproximación eficaz para el manejo del estrés en esta población209210211212.

Terapias individuales

Aunque la evidencia es limitada, dentro de las terapias individuales evaluadas en pacientes con VIH, la psicoterapia interpersonal ha mostrado ser más eficaz que psicoterapia de apoyo o la terapia cognitivo-conductual en el tratamiento de la depresión207.

Recomendaciones

- La formación en estrategias de counseling podría ser de utilidad para todos los profesionales que cuidan de personas con VIH (A-III).

- El uso de estrategias de counselling durante el proceso de trasmisión del diagnóstico de VIH facilitará la adaptación del paciente a la consulta, su aceptación del TAR y permitirá detectar síntomas que requieran valoración por especialistas en salud mental (A-III).

- Estrategias psicoeducativas, como las encaminadas a la prevención de riesgos o a mejorar la adherencia al TAR, podrían ayudar a mejorar la salud mental de las personas con VIH (C-II).

- Las técnicas cognitivo-conductuales (reestructuración cognitiva y técnicas de manejo del estrés) son efectivas en el manejo de estresores asociados al VIH y de la sintomatología ansiosa y depresiva (B-I).

Trastornos psiquiátricos en la población pediátrica

Los niños, niñas y adolescentes que viven con VIH están expuestos a múltiples factores que pueden incrementar su riesgo de tener problemas de salud mental213214. Además de factores biomédicos, sociofamiliares, económico y ambientales, el propio VIH favorece desregulación emocional y conductual al inducir fenómenos de neurotoxicidad a nivel del sistema frontoestriatal215216. Se estima que un tercio de la población pediátrica con VIH puede presentar algún tipo de alteración psicopatológica y que la incidencia de síntomas psicológicos significativos en adolescentes con infección perinatal por VIH podría ser de hasta el 11%217218. Los trastornos más prevalentes en nuestro medio serían la depresión, la ansiedad y el trastorno por déficit de atención219220221. Otros trastornos frecuentes serían las alteraciones del comportamiento y del aprendizaje, así como los déficits a nivel de las funciones ejecutivas y de la velocidad de procesamiento222223224225.

Como ocurre en la población VIH adulta, los trastornos mentales, además de empeorar la calidad de vida, se relaciona con un peor control de la infección, más comportamientos sexuales de riesgo, un mayor consumo de drogas y más dificultades en la transición a servicios de adultos(226–228). Por otra parte, se consideran factores de riesgo para una peor salud mental en menores con VIH: tener alteración de la función cognitiva, la afectación de la salud mental de los cuidadores, experimentar eventos vitales estresantes o vivir en un barrio marginal220.. Los factores que se han considerados protectores serían tener apoyo social, educativo y familiar220.

Diagnóstico

En los menores con VIH, el uso de instrumentos de cribado para la detección de los trastornos mentales favorece su diagnóstico precoz y mejora su pronóstico2. Para detectar depresión disponemos de múltiples instrumentos de cribado validados como el inventario de depresión para niños de Kovacs (CDI)229, la escala para la depresión en adolescentes (RADS)231el HADS231 o el sencillo cuestionario de salud del paciente 2 (PHQ-2)232, capaz de detectar depresión con solo dos preguntas. Para la detección del estigma existe una versión infantil de la escala Berger de VIH y estigma233. Y para otros trastornos como el trastorno por déficit de atención disponemos de escalas como el SNAP IV234 La confirmación del diagnóstico la hará el especialista en psiquiatría y psicología infantil. Existe una versión pediátrica de la entrevista semiestructurada MINI, (MINI-KIDS), que permitiría al especialista en VIH establecer el diagnóstico en la consulta 235.

Tratamiento

Los problemas de salud mental en los menores con VIH están infratratados214217236, probablemente por la falta de una exploración médica rutinaria de los mismos y por problemas de accesibilidad a los recursos de salud mental pediátrica214237. Los estudios disponibles, aunque escasos214238, sugieren que los abordajes psicológicos, como el “Collaborative HIV/AIDS Mental Health Program”, se asocian con mejorías significativas en la salud mental y en síntomas específicos como los depresivos239240241242. La evidencia disponible sugiere beneficios en el tratamiento de los problemas de salud mental en los menores con VIH en servicios de salud mental especializados situados en el mismo

centro que la unidad de VIH y en que se establezcan formulas de enlace y cooperación en la atención entre ambas unidades2. Esta atención multidisciplinar será especialmente importante durante la transición entre las unidades de VIH infantiles y de adultos214237243244

Recomendaciones

- En los menores con VIH se recomienda el uso de instrumentos de cribado para el despistaje precoz de trastornos mentales (A-III).

- El diagnóstico y el tratamiento de trastornos mentales en los menores con VIH debe realizarse en las unidades pediátricas de salud mental (B-III).

- Se recomienda la intervención de especialistas en salud mental durante la transición entre las unidades de VIH infantiles y de adultos (A-III).

Gráficos:

Este cuestionario se ha construido para ayudar a quien le trate a saber cómo se siente usted. Lea cada frase y marque la respuesta que más se ajusta a cómo se sintió usted durante la semana pasada. No piense mucho las respuestas. Lo más seguro es que, si contesta deprisa, sus respuestas podrán reflejar mejor cómo se encontraba usted durante la semana pasada. (Mire la página siguiente para realizar el cuestionario).

Interpretación

La escala está formada por catorce ítems, siete de los cuales miden la ansiedad y los otros siete la depresión (los ítems que miden la depresión están marcados con un asterisco). Cada ítem puntúa de 0 a 3 (de menos a más patología). Las respuestas de las preguntas 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, y 13 se puntúan de la siguiente forma: 3 puntos la primera respuesta, 2 puntos la segunda, 1 punto la tercera y 0 puntos la cuarta. Las respuestas de las preguntas 2, 4, 7, 9, 12, y 14 se puntúan de la siguiente forma: 0 puntos la primera respuesta, 1 punto la segunda, 2 puntos la tercera y 3 puntos la cuarta. Se considera que por debajo de 7 puntos no hay patología, entre 8 y 10 es dudosa, y si es mayor de 10 es indicativa de patología ansiosa o depresiva.

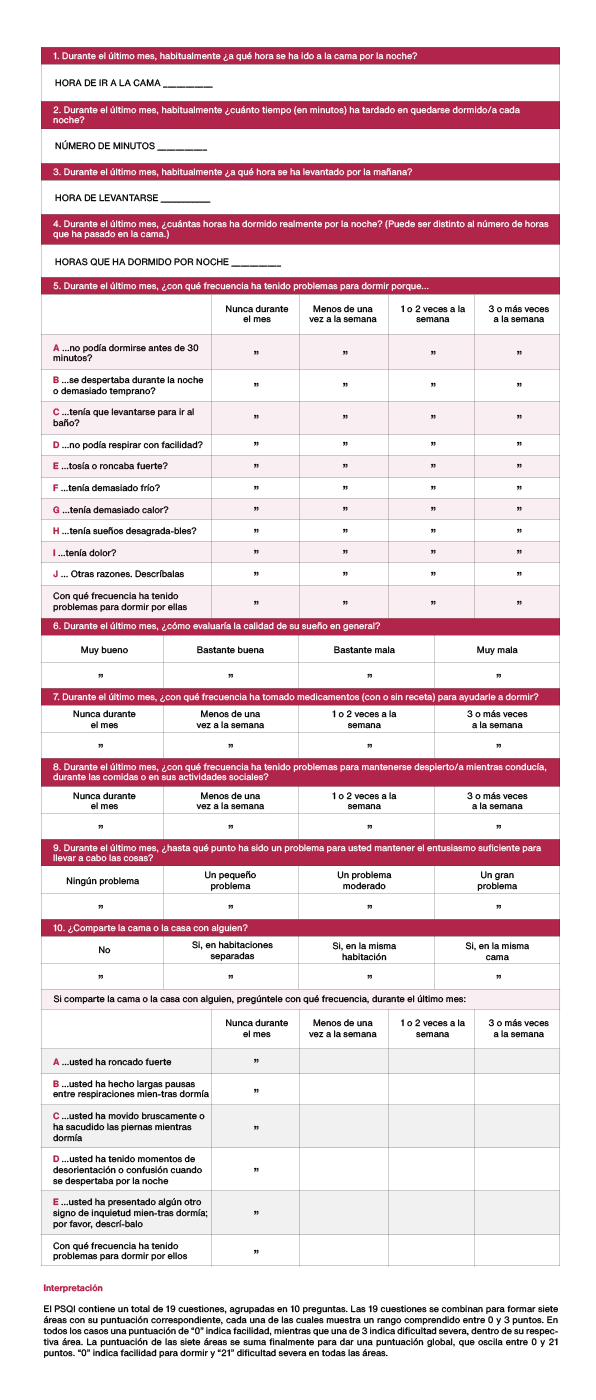

(Spanish version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index – PSQI)

INSTRUCCIONES: Las siguientes preguntas tratan sobre sus hábitos generales de sueño solamente durante el último mes (los últimos 30 días). Sus respuestas deberán ser lo más precisas posible para la mayoría de los días y noches del último mes. Por favor, conteste a todas las preguntas.

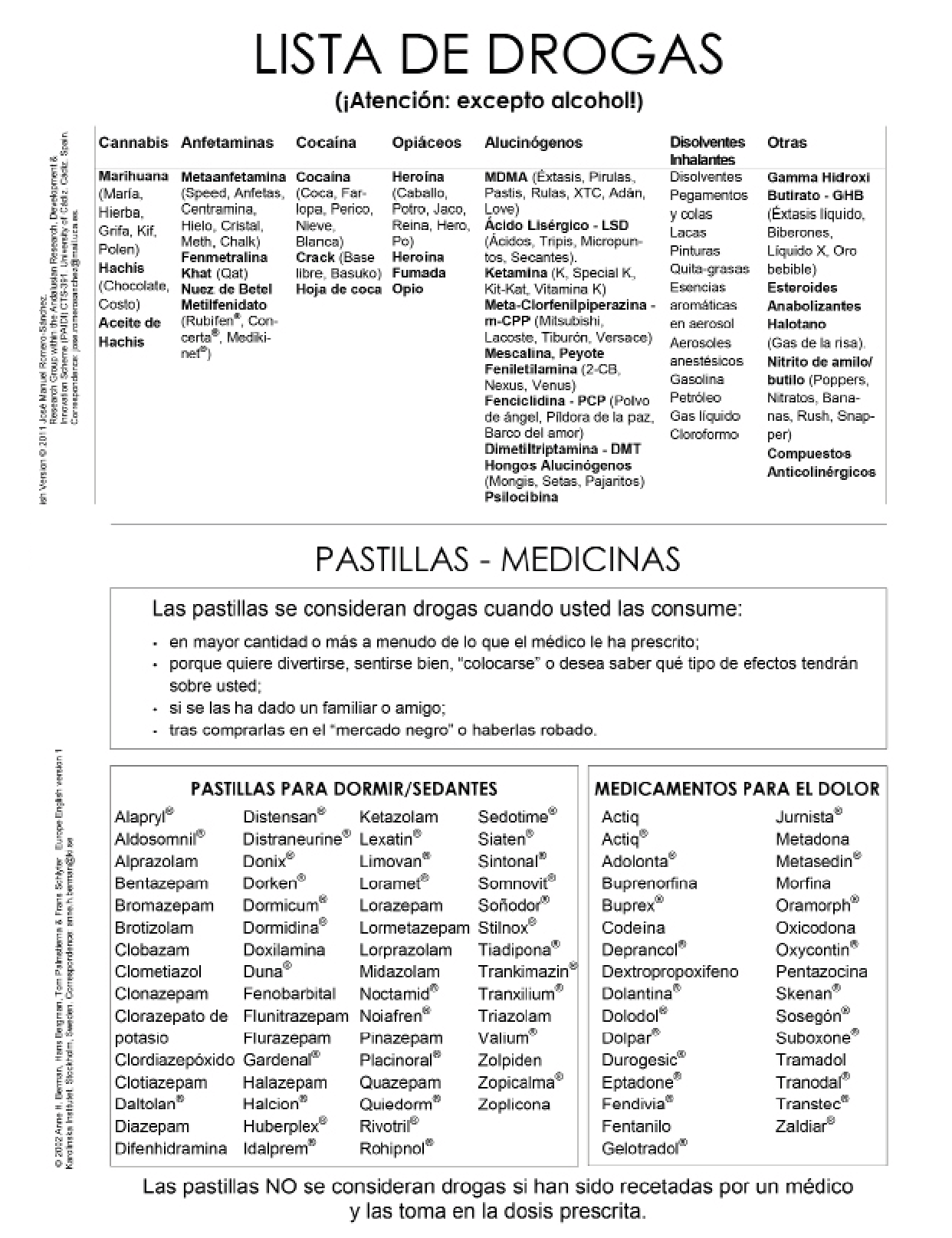

Interpretación DUDIT

Las preguntas 1-9 de la prueba puntúan entre 0 y 4 puntos cada una en función de la respuesta dada (primera columna – 0 puntos, segunda columna – 1 punto, tercera columna

– 2 puntos, cuarta columna – 3 puntos y quinta columna – 4 puntos). Y las preguntas 10-11 de la prueba puntúan entre 0, 2 o 4 puntos cada una en función de la respuesta dada (primera columna – 0 puntos, segunda columna – 2 puntos y tercera columna – 4 puntos). Una puntuación de >6 puntos en hombres y de >2 puntos en mujeres sugieren la existencia de un posible consumo problemático de una o más drogas. Puntuaciones de

>25 puntos es indicativa de probable dependencia a una o más drogas.

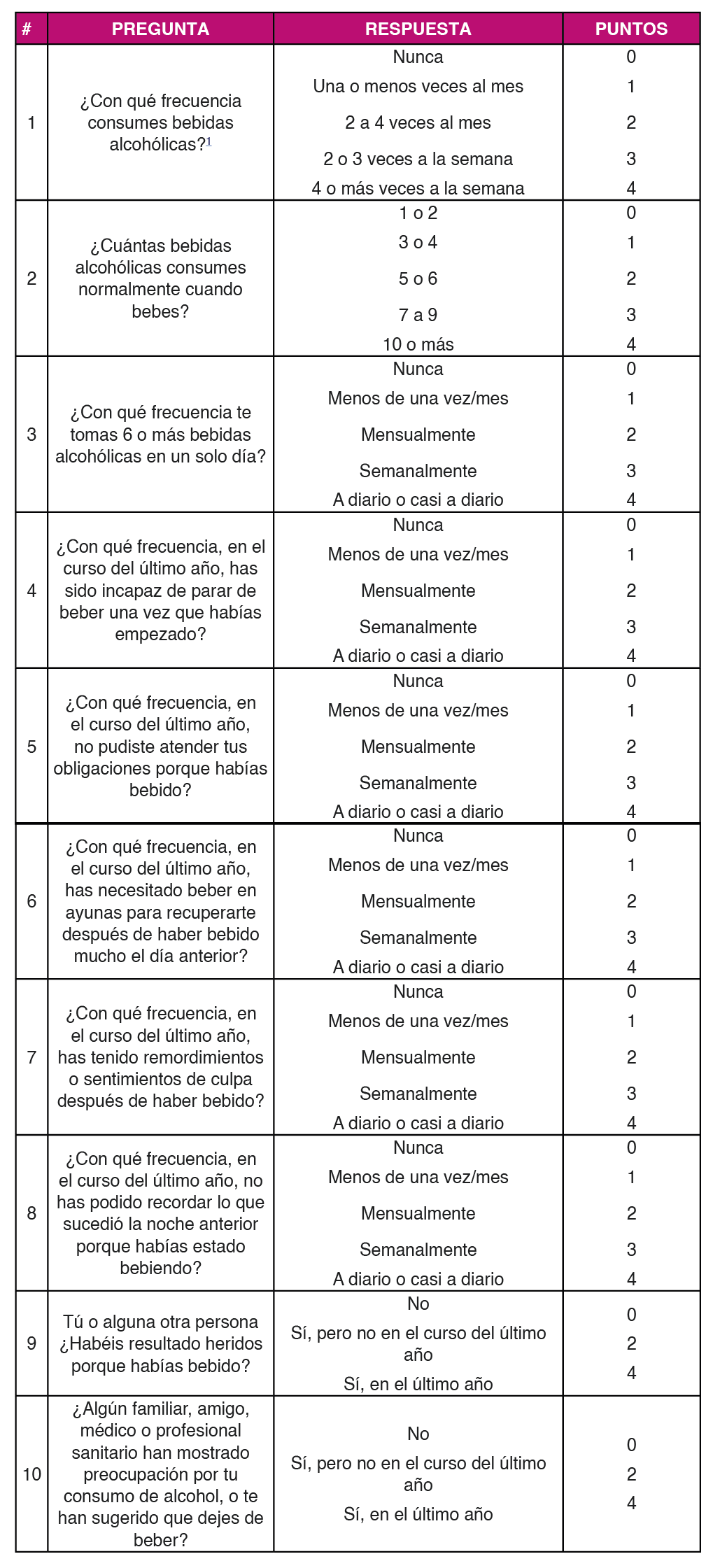

Interpretación AUDIT

La puntuación global de la prueba se obtendrá al sumar la puntuación otorgada a cada una de las 10 preguntas de la prueba. Una puntuación de >8 en hombres, o de >7 en mujeres, indica una fuerte probabilidad de daños debido al consumo de alcohol. Un puntaje de 20 o más sugiere una dependencia del alcohol. Una puntuación >13 en mujeres y >15 en hombres es indicativa de probable dependencia al alcohol.

* Elaborado por Spitzer RL y col. mediante una subvención educativa otorgada por Pfizer Inc. No se requiere permisos para reproducir, traducir, presentar o distribuir.

Interpretación

Si hay >4 respuestas en las columnas “mas de la mitad de los días” o “casi todos los días” (incluyendo las preguntas 1 y 2) o >5 (incluyendo la pregunta 1 o la 2), considerar un trastorno depresivo mayor. Sumar las puntuaciones para valorar la severidad (<10 leve, 10- 14 moderado, 15-19 moderado-severo y >20 severo). Considerar otro trastorno depresivo cuando el número de respuestas en las columnas “más de la mitad de los días” o “casi todos los días” sea entre 2-4 (cuando una de esas respuestas corresponde a las preguntas 1 o 2).

Tablas:

Bibliografía:

Cantú Guzmán R, Álvarez Bermúdez J, Torres López E, Martínez Sulvarán O. Impacto psicosocial asociado al diagnóstico de infección por vih/SIDA: apartados cualitativos de medición. Revista Electrónica Medicina, Salud y Published online 2012.

Flowers P, Davis MM, Larkin M, Church S, Marriott C. Understanding the impact of HIV diagnosis amongst gay men in Scotland: An interpretative phenomenological Psychology & Health. 2011;26(10):1378-1391. doi:10.1080/08870446.2010.551213

Zeligman M, Wood AW. Conceptualizing an HIV Diagnosis Through a Model of Grief and Adultspan Journal. 2017;16(1):18-30. doi:10.1002/adsp.12031

Richard Lazarus MVMSF. Estrés y Procesos Cognitivos. (Martinez Roca, ed.).; 1986.

Milena Gaviria A, Quiceno JM, Vinaccia S, Martínez LA, Otalvaro Estrategias de afrontamiento y ansiedad-depresión en pacientes diagnosticados con VIH/SIDA. Terapia Psicologica. 2009;27(1):5-13. doi:10.4067/s0718-48082009000100001

Carrobles JA, Remor E, Rodríguez-Alzamora Afrontamiento, apoyo social percibido y distrés emocional en pacientes con infección por VIH. [Relationshiop of coping and perceived social support to emotional distress in people living with HIV.]. Psicothema. 2003;15(3):420-426.

Chida Y, Vedhara Adverse psychosocial factors predict poorer prognosis in HIV disease: A meta- analytic review of prospective investigations. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23(4):434-445. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.013

Ironson GH, O’Cleirigh C, Weiss A, Schneiderman N, Costa PT. Personality and HIV Disease Progression: Role of NEO-PI-R Openness, Extraversion, and Profiles of Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(2):245-253. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816422fc

Lee RS, Kochman A, Sikkema Internalized Stigma Among People Living with HIV-AIDS. AIDS

Guevara-Sotelo Y, Hoyos-Hernández Vivir con VIH: experiencias de estigma sentido en

Chan RCH, Mak WWS. Cognitive, Regulatory, and Interpersonal Mechanisms of HIV Stigma on the Mental and Social Health of Men Who Have Sex With Men Living With HIV. American Journal of Men’s 2019;13(5):155798831987377. doi:10.1177/1557988319873778

Travaglini LE, Himelhoch SS, Fang LJ. HIV Stigma and Its Relation to Mental, Physical and Social Health Among Black Women Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(12):3783-3794. doi:10.1007/s10461-018-2037-1

Atkinson JS, Nilsson Schönnesson L, Williams ML, Timpson Associations among correlates of schedule adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): A path analysis of a sample of crack cocaine using sexually active African–Americans with HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2008;20(2):253- 262. doi:10.1080/09540120701506788

Johnson CJ, Heckman TG, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Adherence to antiretroviral medication in older adults living with HIV/AIDS: a comparison of alternative models. AIDS Care. 2009;21(5):541-551. doi:10.1080/09540120802385611

Santoro Pablo CF. Tipos de problemas de adherencia entre las personas con VIH y tendencias emergentes en la adherencia al tratamiento antirretroviral (TAR). Revista Multidisciplinar del 2013;1(1):41-58.

Dilla T, Valladares A, Lizán L, Sacristán JA. Adherencia y persistencia terapéutica: causas, consecuencias y estrategias de mejora. Atención Primaria. 2009;41(6):342-348. doi:10.1016/j. 2008.09.031

Owe-Larsson M, Säll L, Salamon E, Allgulander HIV infection and psychiatric illness. African

Dyer JG and Reducing HIV risk among people with serious mental illness. J

Parhami I, Fong TW, Siani A, Carlotti C, Khanlou H. Documentation of Psychiatric Disorders and Related Factors in a Large Sample Population of HIV-Positive Patients in California. AIDS and 2013;17(8):2792-2801. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0386-8

Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric Disorders and Drug Use Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Infected Adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721

Lopes M, Olfson M, Rabkin J, et Gender, HIV Status, and Psychiatric Disorders. The Journal of

Brandt The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: A systematic review. African

Burnam MA, Bing EG, Morton SC, et Use of mental health and substance abuse treatment services among adults with HIV in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):729-736. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.729

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

Schadé A, van Grootheest G, Smit JH. HIV-infected mental health patients: Characteristics and comparison with HIV-infected patients from the general population and non-infected mental health BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-35

Gallego L, Barreiro P, Lopez-Ibor Diagnosis and Clinical Features of Major Neuropsychiatric

Pence BW, O’Donnell JK, Gaynes Falling through the cracks. AIDS. 2012;26(5):656-658.

Beer L, Tie Y, Padilla M, Shouse Generalized anxiety disorder symptoms among persons with diagnosed HIV in the United States. AIDS. 2019;33(11):1781-1787. doi:10.1097/ QAD.0000000000002286

Rane MS, Hong T, Govere S, et al. Depression and Anxiety as Risk Factors for Delayed Care- Seeking Behavior in Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Infected Individuals in South Africa. Clinical Infectious 2018;67(9):1411-1418. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy309

Glynn TR, Safren SA, Carrico AW, et al. High Levels of Syndemics and Their Association with Adherence, Viral Non-suppression, and Biobehavioral Transmission Risk in Miami, a S. City with an HIV/AIDS Epidemic. AIDS and Behavior. 2019;23(11):2956-2965. doi:10.1007/s10461-019- 02619-0

Been SK, Schadé A, Bassant N, Kastelijns M, Pogány K, Verbon A. Anxiety, depression and treatment adherence among HIV-infected AIDS Care. 2019;31(8):979-987. doi:10.1080/ 09540121.2019.1601676

Zigmond AS, Snaith The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica

Ferrando L, Bobes J Gibert M, Soto M, Soto M.I.N.I. Mini International Neuropsychiatric

Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, Evidence-basedguidelinesforthepharmacologicaltreatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2005;19(6):567-596. doi:10.1177/0269881105059253

Rabkin HIV and depression: 2008 review and update. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2008;5(4):163-

doi:10.1007/s11904-008-0025-1

Leserman HIV disease progression: depression, stress, and possible mechanisms. Biological

Mollan KR, Smurzynski M, Eron JJ, et Association Between Efavirenz as Initial Therapy for HIV- 1 Infection and Increased Risk for Suicidal Ideation or Attempted or Completed Suicide. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;161(1):1. doi:10.7326/M14-0293

Slot M, Sodemann M, Gabel C, Holmskov J, Laursen T, Rodkjaer Factors associated with risk of depression and relevant predictors of screening for depression in clinical practice: a cross- sectional study among HIV-infected individuals in Denmark. HIV Medicine. 2015;16(7):393-402. doi:10.1111/hiv.12223

Robertson K, Bayon C, Molina J-M, et al. Screening for neurocognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety in HIV-infected patients in Western Europe and AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1555- 1561. doi:10.1080/09540121.2014.936813

Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Have T ten, et al. Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in Women With HIV

Rao D, Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, et al. A Structural Equation Model of HIV-Related Stigma, Depressive Symptoms, and Medication Adherence. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(3):711-716. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-9915-0

Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between HIV Infection and Risk for Depressive Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):725-730. doi:10.1176/appi. 158.5.725

Tegger MK, Crane HM, Tapia KA, Uldall KK, Holte SE, Kitahata MM. The Effect of Mental Illness, Substance Use, and Treatment for Depression on the Initiation of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Infected Individuals. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(3):233-243. doi:10.1089/apc.2007.0092

Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, Safren Depression and HIV/AIDS Treatment Nonadherence: A Review and Meta-analysis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;58(2):181-187. doi:10.1097/QAI.0B013E31822D490A

Springer SA, Dushaj A, Azar MM. The Impact of DSM-IV Mental Disorders on Adherence to Combination Antiretroviral Therapy Among Adult Persons Living with HIV/AIDS: A Systematic AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(8):2119-2143. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0212-3

Sherr L, Clucas C, Harding R, Sibley E, Catalan J. HIV and Depression – a systematic review of Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16(5):493-527. doi:10.1080/13548506.2011.5 79990

Leserman Role of Depression, Stress, and Trauma in HIV Disease Progression. Psychosomatic

So‐Armah K, Gupta S, Kundu S, et Depression and all‐cause mortality risk in HIV‐infected and HIV‐uninfected US veterans: a cohort study. HIV Medicine. 2019;20(5):317-329. doi:10.1111/ hiv.12726

European AIDS Clinical Society. EACS Guidelines version 10.0 — EACS. Published November Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.eacsociety.org/files/2019_guidelines-10.0_final.pdf.

Treisman GJ, Soudry O. Neuropsychiatric Effects of HIV Antiviral Medications. Drug Safety. 2016;39(10):945-957. doi:10.1007/s40264-016-0440-y

Aragonès E, Roca M, Mora F. Abordaje Compartido de La Depresión: Consenso Multidisciplinar ; 2018. Accessed June 25, 2020. Ebook disponible en: www.semfyc.es/wp-content/ uploads/2018/05/ Consenso_depresion.pdf.

Laperriere A, Ironson GH, Antoni MH, et al. Decreased Depression Up to One Year Following CBSM+ Intervention in Depressed Women with AIDS: The Smart/EST Women’s Project. Journal of Health 2005;10(2):223-231. doi:10.1177/1359105305049772

Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Durán RE, et Reductions in depressed mood and denial coping during

Paulus DJ, Brandt CP, Lemaire C, Zvolensky MJ. Trajectory of change in anxiety sensitivity in relation to anxiety, depression, and quality of life among persons living with HIV/AIDS following transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2020;49(2):149-163. doi:10.1080/16506073.2019.1621929

Freudenreich O, Goforth HW, Cozza KL, et Psychiatric treatment of persons with HIV/AIDS: An HIV-psychiatry consensus survey of current practices. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(6):480-488. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.51.6.480

Ferrando SJ, Freyberg Treatment of depression in HIV positive individuals: A critical review.

Chandra PS, Desai G, Ranjan HIV & Psychiatric Disorders. Vol 121.; 2005.

de Sousa Gurgel W, da Silva Carneiro AH, Barreto Rebouças D, Negreiros de Matos KJ, do Menino Jesus Silva Leitão T, de Matos e Souza FG. Prevalence of bipolar disorder in a HIV- infected outpatient AIDS Care. 2013;25(12):1499-1503. doi:10.1080/09540121.2013.7 79625

Kieburtz K, Zettelmaier AE, Ketonen L, Tuite M, Caine Manic syndrome in AIDS. American

Ellen SR, Judd FK, Mijch AM, Cockram Secondary Mania in Patients with HIV Infection. Australian

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Musisi S, Mpungu SK, Katabira Primary Mania Versus HIV-Related Secondary Mania in Uganda. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1349-1354. doi:10.1176/ ajp.2006.163.8.1349

Robinson Primary Mania Versus Secondary Mania of HIV/AIDS in Uganda. American Journal

Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Musisi S, Kiwuwa Mpungu S, Katabira E. Clinical Presentation of Bipolar Mania in HIV-Positive Patients in Psychosomatics. 2009;50(4):325-330. doi:10.1176/appi. psy.50.4.325

Lyketsos CG, Hanson AL, Fishman M, Rosenblatt A, McHugh PR, Treisman GJ. Manic syndrome early and late in the course of HIV. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150(2):326-327. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.2.326

Nakimuli-Mpungu, Mutamba Brian, Nshemerirwe Slyvia, Kiwuwa Mpungu Steven, Seggane Musisi. Effect of HIV infection on time to recovery from an acute manic HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care. 2010;2:185. doi:10.2147/hiv.s9978

Soares Recent advances in the treatment of bipolar mania, depression, mixed states, and rapid cycling. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;15(4):183-196. doi:10.1097/00004850- 200015040-00001

American Psychiatric Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5

Stolar A. HIV and Psychiatry, Second Edition: A Training and Resource Manual . Cambridge University Press;

Newton PJ, Newsholme W, Brink NS, Manji H, Williams IG, Miller RF. Acute meningoencephalitis and meningitis due to primary HIV infection. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2002;325(7374):1225- https://Pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12446542

Anguizola-Tamayo D, Bocos-Portillo J, Pardina-Vilella L, et al. Psychosis of dual origin in HIV infection: Viral escape syndrome and autoimmune encephalitis. Neurology Clinical practice. 2019;9(2):178-180. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000582

Laher A, Ariefdien N, Etlouba HIV prevalence among first-presentation psychotic patients. HIV

de Ronchi D, Faranca I, Forti P, et al. Development of Acute Psychotic Disorders and HIV-1 The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2000;30(2):173-183. doi:10.2190/ PLGX-N48F-RBHJ-UF8K

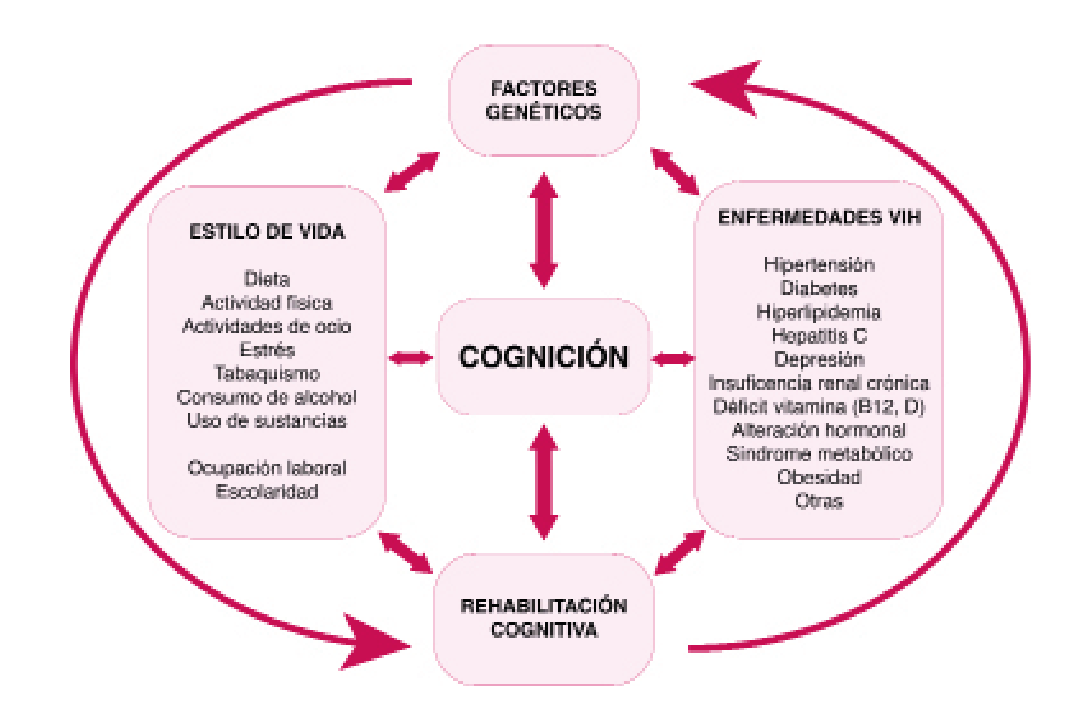

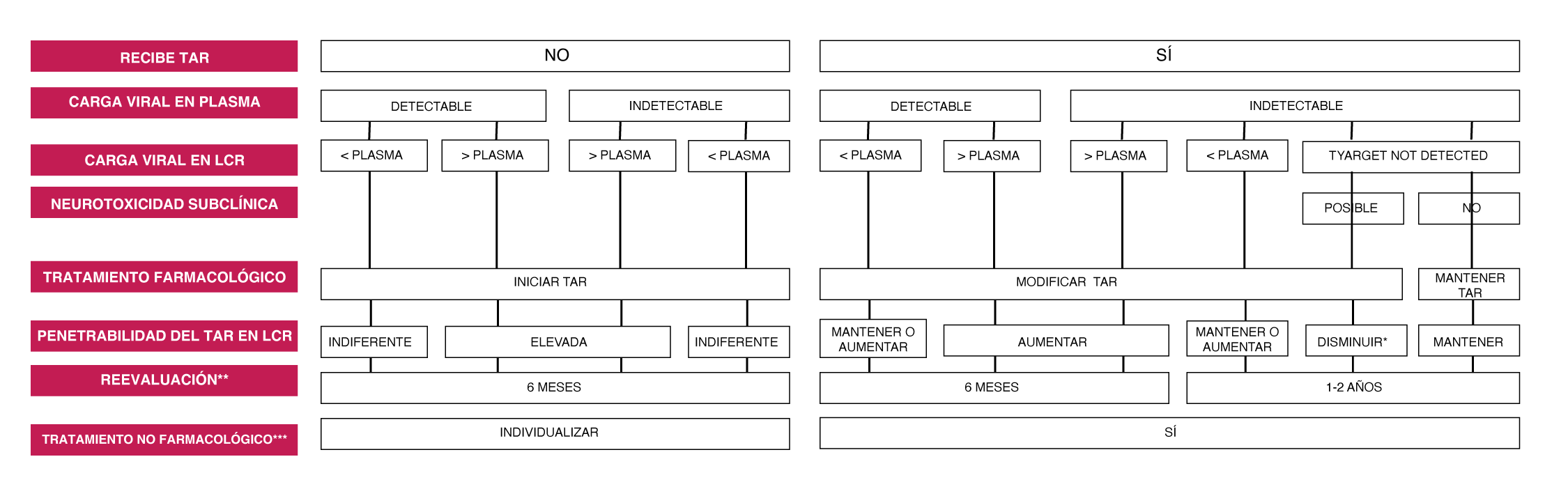

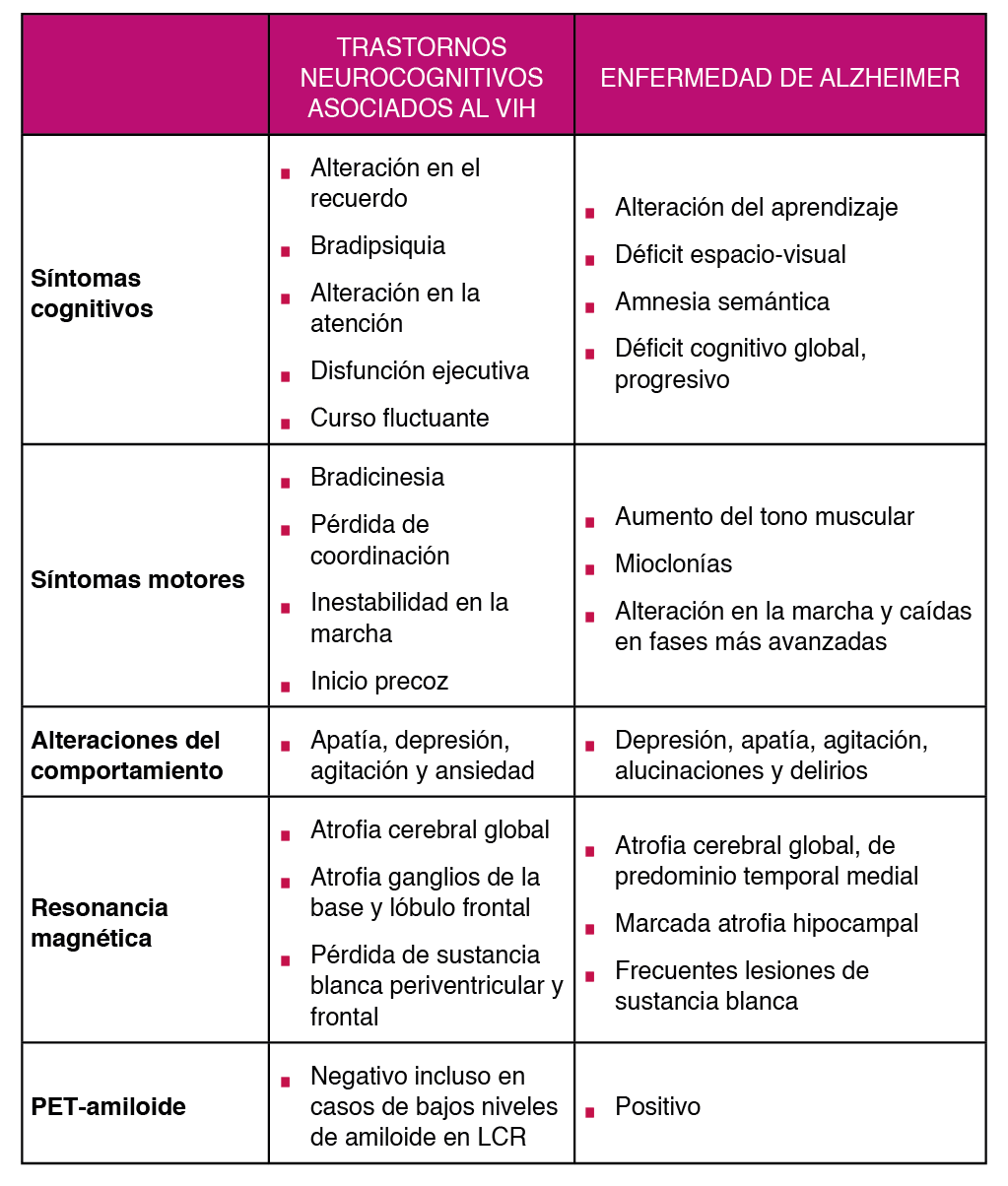

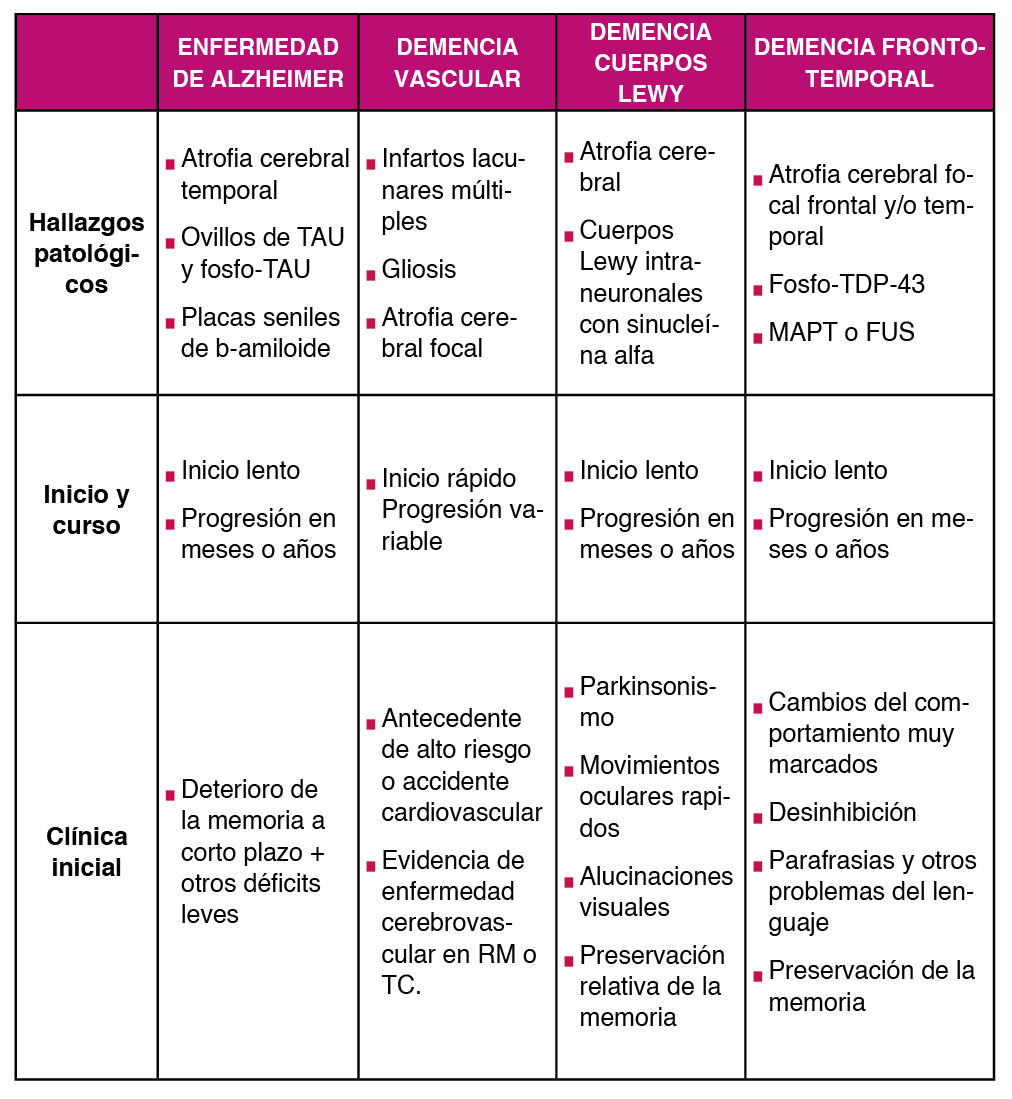

Singh AN, Golledge H, Catalan Treatment of HIV-related psychotic disorders with risperidone: A series of 21 cases. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1997;42(5):489-493. doi:10.1016/S0022- 3999(96)00373-X